Race & Class - Catching History on the Wing

![]() |

| Grunwick - the most important Black working class struggle in Britain - attacked by the courts and Lord Denning and betrayed by the TUC and Labour establishment - was at the heart of Siva's analysis |

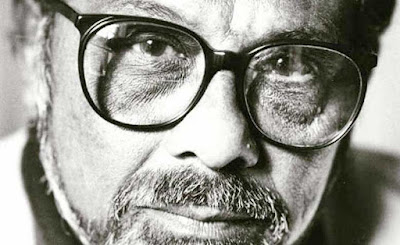

Like many people active in the anti-racist and anti-fascist movement, I was profoundly influenced by Siva. Many were the discussions we had at Leeke Street. I first saw Siva speak when he appeared at a Conference organised by Searchlight in the days when the anti-fascist magazine, under the editorship of Maurice Ludmer, was trusted by the anti-fascist movement, i.e. the days before Gerry Gable became editor.

Siva built up the Institute of Race Relations after a coup against its liberal ruling class trustees. He never tired of telling how Paul Foot, the public school scion of the oh so revolutionary International Socialists Group (SWP) had supported the old liberal establishment.

I first came into contact with Siva and the rest of the Race and Class collective through my involvement with Anti-Fascist Action in the mid-1980s. Siva was our guide and our mentor in his criticisms of the race relations industry and how they were trying to co-opt anti-racist and Black struggles. It was a time when identity politics was starting to rear its head.

Now anyone could claim, by virtue of their identity, that they too were oppressed. Zionist feminism and the belief that all you need to do was celebrate who you thought you were, even if it was at someone else’s expense, was at the heart of debate that split Spare Rib, the feminist magazine. We took to heart his saying that ‘What we do is what we are.” *.

Race and Class provided a welcome commentary with its incisive analysis of anti-racist and anti-imperialist politics. Without a class analysis and component anti-racism inevitably meant a reformist adaption to the system.

It was a welcome counterpoint to the then fashionable identity politics which were a way of internalising campaigns and politics and making the focus of change the individual rather than the structures of society. People in the Labour Party were using the Black anti-racist struggle outside the party as a means of advancing the careers of people like Keith Vaz. I came across this quite recently when I found that an old comrade from anti-fascist days, Unmesh Desai, was now a Labour member for Newham of the Greater London Authority and in that role he had supported the Zionist IHRA definition of ‘anti-Semitism’ which conflates anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism.

I remember attending one particular meeting at the IRR base at Leeke Street where the renowned Israeli anti-Zionist and civil rights activist, Professor Israel Shahak gave a talk. Shahak had been a childhoold survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto and Belsen concentration camps. The Institute had always been prominent in supporting the struggle of the Palestinians for liberation and in its opposition to Zionism, seeing clearly that as Apartheid in South Africa was on its way out, Apartheid in Israel was being strengthened and reinforced.

Many are the happy memories of paying the Institute a visit when I was in London and breaking bread with them and looking through their extensive newspaper library.

In the mid 1980’s I did a long interview with Siva for London Labour Briefing and then had a big battle to get it into the paper as anti-racism took second place to internal Labour Party and personal politics.

When multi culturalism was in vogue and the State moved from repression to incorporation of Black struggle Siva was a lone voice warning against the dangers of co-option of the anti-racist movement and its leadership. He was a particularly strident critic of Racism Awareness Training which was, he argued, a means by which the Police would get to know their enemy better. The whole race relations industry was geared towards diffusing any fight against the capitalist system.

Siva argued that multi-culturalism was a means of diverting the anti-racist struggle into cultural difference, of depoliticising it. However in the 1990’s under New Labour we saw a political attack on multi-culturalism which continues to this day as the State , in the wake of the Iraq war, moved to demonise whole sections of the Black and Asian population.

I will remember Siva with fondness and as someone with a great sense of humour.

Tony Greenstein

·

A Sivanandan, Culture and Identity, Liberator, New York, Vol. 10. No. 6 1970

Daniel Renwick calls for the whole movement to discover and remember the vital work of A. Sivanandan, who died this week

Red Pepper, January 6, 2018

Ambalavaner Sivanandan (Siva) was not en vogue during my life. For activists and anti-racist campaigners of previous generations of the black struggle, though, Siva was a giant.

His presence was announced in so many ways: his polemic pamphlets

launched like grenades into key battles like Grunwick. When you chart the struggles in Britain, and the writings, debates and interventions around them, Siva’s influence can be felt. However, with the changes that came with globalism, Thatcherism and financialisation, the uncompromising position he held meant he was sometimes seen as somebody who was stuck in the paradigms of yesteryear – a shocking misconception that needs rectifying now more than ever.

For Siva to have an influence in modern struggles, people have to know his name and seek out his work. Only radical veterans, generally outside of the academe, spoke of his immeasurable influence. The new generations of anti-racists didn’t seem to know him, even if they used his aphorisms.

Capitalism’s furnace

Siva made penetrating interventions on the issues that define our political moment. While he never used a computer, writing all of his works by hand, he understood what the microchip had done to global class relations more than the writers who embraced the technological revolution, which Siva recognised had a greater impact on human relations than the industrial revolution.

What Silicon Valley and the microchip enabled, Siva noted with great incision, was the shift of capitalism’s furnace, from the metropole to the periphery. Modern technology freed capital from labour, not the other way around. Automation and mechanisation put a proverbial gun to the head of the worker, empowering multinational corporations to eviscerate working conditions in a race to the bottom. Resistance from states or social movements seeking to curtail the power of multinational corporations meant they upped sticks and moved their plants to other, more pliable nation states or localities, where new populations were grist to the mill.

Globalism,

Siva noted with force, was a project; globalisation was the process. With the fall of the Soviet Union, the world and social movements came to know ‘TINA’ (there is no alternative). This is what Mark Fisher later called ‘capitalist realism’ – the sense that resistance is futile and the world must learn to accept and embrace global capitalism.

For many, there was something to celebrate in this. The planned economies and political centralisation that communism bred into resistance movements had made it too cumbersome and flat-footed, but to Siva, conceding the ground of economic alternatives was a crime that could not be excused.

To find salvation in identity, dress, fashion and plurality, while billions were impoverished by a global system was ‘hokum’. Stuart Hall, a friend and interlocutor of Siva and the Institute of Race Relations, was dealt caustic blow after caustic blow for his embracing of the ‘new times’, which Siva cut through as ‘Thatcherism in drag’. If you got on the wrong side of Siva politically, you would know it. He did not compromise.

It wasn’t just that political visions must be maintained, but that the mutations of history must be mapped, and systems of resistance to be re-imagined. Globalism made the distinction between economic migrant and refugee fatuous. The crises around the world around borders and migrations illustrate Siva’s point remarkably. Globalism tore the fabric of nation states to pieces and worsened living conditions, making emigration a necessity to those seeking betterment of their lives. Immigration to the West is therefore bound to what the West is doing abroad. The structural violence of the World Bank and the physical violence of NATO were two sides of the same coin that pushed millions to traverse borders. His maxim about the presence of former colonial subjects in the West can be re-read in the conditions of the present:

‘we are here because you were there’. Mass migrations continue on the basis of power dynamics based on colonial and imperial logics. Another of his great sayings comes to mind: ‘colonialism is not over, it is all over’.

Siva was a thinker who cut to the bone on the issues of migration, automation, globalism, identity politics, class and race. It is a scandal to me that those who claim to be versed in the schools of anti-racism are not screaming his name from the rooftops and making social media reverberate with his legacy. But such are the times. Siva did not write for the social media warrior. He did not concern himself with the race politics of representation. ‘The people we write for are the people we fight for,’ that was his school. He did not seek to put a veneer over a violent present – he sought to rip down the veil and push people to take action that empowered and amplified those at the coal face of the struggle. He encouraged people to work on lived theory – where social theory and academia engaged with the material conditions of those most persecuted and oppressed.

Water in a desert

The writings of Sivanandan are for me like water in a desert. His words encourage a criticality and fuel an anger to challenge a violent present, predicated on an even more violent past. While many writers fall into bad faith, convincing themselves that positive change can emerge through compromise, Siva encouraged radical and profound resistance to the world from the bottom up.

Identity, in and of itself, was a cul de sac. Racism, in his analysis, was a global class system that could only be overcome through major structural change.

Diversity within the existing system was not progress to Siva. White navel gazing was mercilessly mocked with his engagement with racial awareness training, which he claimed reified race relations and locked whites into a mode of self-flagellation, when they should be encouraged to challenge the status quo and stand in solidarity with those on the picket lines, being deported or being held at detention centres. Switch a few referents and you have a profound engagement with the culture of allyship that underwrites white engagement with anti-racism in the modern day. ‘Who you are is what you do,’ he told whites who wanted to be part of anti-racist struggle, opening up the possibility of meaningful political engagement for those seeking a better world.

Many of those who loved and admired Siva have humorous stories of their first encounter with the man, his uncompromising engagement that was intimidating, to say the least, both intellectually and physically. He helped to teach so many lessons, and push the struggle forwards.

History, for Siva, was a dialectic. He did not confine this to the dialectal materialism of the dogmatic Marxists: he brought

the Bhagavad Gita and TS Eliot to his dialectical analysis. The discursive turn taken in the late 20th century that made language the site of struggle frustrated him. Language was not the battleground, the world was. Structures needed to be changed, not language. Truths needed to be spoken, not narratives. He eschewed the idea that the personal was a realm for the political, reversing the dictum by saying the ‘the political is always personal’. Siva taught that political struggle is based on fighting with those who are the victims of the system and saw no merit in moving the furniture or window-dressing the butcher’s house.

The people influenced by him may not be as numerous as they should be now, but the tools he provided mean that many people are still trained to take aim at history. History, Siva told Colin Prescod in an interview a few years ago, is now moving too fast to catch on the wing, something any casual watcher of the news knows only too well. The task we have is to find where we can puncture the moment, where struggle worthy of the word can be forged and the system can be challenged.

For Siva, and those who follow him, this is as local as it is global. It is fighting to keep a local library, it is fighting for public space, it is fighting against deportations, it is standing in solidarity in Calais, it is fighting the struggle in the wake of the Grenfell fire, it is standing firm against nativism and border politics when the colonial past casts such a deep shadow over our present.

To end on one of his most powerful aphorisms, ‘If those who have do not give, those who haven’t must take.’

An essay written during the middle of the Grunwicks strike in Willesden, north-west London. A predominatly east African Asian female workforce went on strike against poor conditions and for union recognition.

There were mass pickets, sometimes violent, in support of the strikers. They eventually became disillusioned with the half-hearted and obstructive role of the unions and, towards the end of the defeated strike, conducted a hunger strike/picket outside the TUC headquarters.

A Sivanandan, Siva to everyone who knew him, is a huge loss to the British, and indeed the international socialist, anti-racist and anti-imperialist left, but has left us a tremendous legacy in his great range of writings, the journal

Race and Class, and the

Institute of Race Relations. This last was once a government, and establishment body, but Siva and his allies famously staged a ‘palace coup’ (as he sometimes referred to it, although it was an exemplarily democratic process), and revolutionised it into the radical institution it has been since the early 1970s.

In the mid-eighties, during the demonization of radicals in general as the ‘Looney Left’, there were enough caricatures of anti-racism in particular flowing about that, as a teenager, new to London and the UK, I heard of Siva himself as some sort of self-important and threatening eminence. Not long afterwards, I was lucky enough to meet the man. The contrast between the generous, witty, and wise human reality and the slander could not have been greater. This was, if it were ever needed, a lesson in how figures on the left, and particularly an unapologetic black voicedenouncing racial injustice, are routinely denigrated in order to dismiss the importance of the cause.

The summary story Siva himself told of his life began as a boy in a Tamil village in Sri Lanka, then as a man coming to London in the midst of the ‘race riots’ of 1958 (racist riots, that is to say). His concerns were always to link the experiences of Empire and neo-imperialism to the nature of politics in the first world. The many peoples exploited and oppressed historically and in the present by imperial nations like Britain meant that for Siva ‘Black’ was a ‘political colour’ which ought to produce solidarities against the racist structures of capitalism.

Siva’s legacy is a rich one, which his many writings will continue to make accessible to a wide audience (see for example the essay collections, A Different Hunger, 1982, Communities of Resistance, 1990, and Catching History on the Wing, 2008). Siva’s writing encompassed a huge range of subjects, from economic analysis to the consideration of cultural figures, but of course the threads of race and imperialism tie them all together. His was an activist’s perspective, demanding that, as he said, we should think in order to do, not think in order to think. Yet his writing was hardly utilitarian in nature. Siva’s poetic inclination was evident in all his polemical and analytical writing, so it was no surprise when the novel on which he worked for many years, When Memory Dies, was published, it proved to be a triumph of sensibility and craft, a deeply realised historical portrait of racism and violence, but also of solidarities and hope, in Sri Lanka.

Siva was most widely known for his writings on racism and black history in Britain, and his and the IRR’s analysis of ‘institutional racism’ reached its widest recognition with the inclusion of a version, at least, of the concept in the Macpherson Report of 1999. Like so many examples of left-analysis, it might well be thought that this was more honoured in the breach than the observance, but it was an important moment in the recognition of the nature of racism in Britain. The point is not so much the existence of personal prejudice, but the social and state structures which create a racially unequal society.

He was thus a critic of ‘racism awareness training’ of the 1980s as it personalised the problem, and reduced a question of structural inequality requiring real changes to the economic structure of society, and to the nature of the state in Britain, to a question of individual psychology. It removed responsibility for racism from the state and society to the individual level. Thus he once explained that he did notwant white British people to feel guilt, but rather to experience shamefor the racism of the British state and its history. Guilt, he elaborated, was something that was internalised and lead to paralysis at best. Shame, in contrast, was an outward looking emotion that could motivate someone to demand change and social justice in the outside world, and would not waste energy in internalised agonies. He explained all this in far more graceful and captivating terms than I am able to reproduce here, but I hope the wisdom of it is apparent.

Siva’s analysis of race was crucially bound up with class and imperialist structures, and resisted being reduced to the personalised or individualised. I recall him observing that the phrase of the 1960s, the ‘personal is political’ should be understood in the sense that the ‘political is personal’. When politicians make inflammatory comments about immigrants or about race, then the political becomes very personal to the victims of the racist violence which inevitably follows.

In the early 1990s he became an outspoken critic of the postmodernist turn of radical politics, in a trenchant and brilliant piece on the so-called ‘New Times’ analysis (‘All that melts into air is solid: the hokum of New Times’, Race and Class, vol. 31, 1990, pp.1-30). This tendency that emerged from the decaying Communist Party was a precursor of the Blairites, and indeed in many real senses prepared the ground for them amongst part of the left. Siva’s critique was therefore timely and incisive. Siva always recognised the subjective side of political struggle, once writing that there ‘is no set-back in history except that we make it so’ (A Different Hunger, p.68). However, here he clarified its limits, and demonstrated the continuing importance of the key elements of Marxist analysis to an analysis of capitalism and racism in the so-called new times of the 1990s.

Siva’s argument was clearly borne out as the years passed. Siva’s vision of solidarity against the structures of racism and capitalism, both among the masses within the imperial ‘core’ and within all the countries on the sharp end of imperialist violence and exploitation, has lost none of its urgency across the years. Siva’s understanding of race, class and imperialism, and of humanity in general, will continue to inspire resistance to injustice and hope for socialism.

Two interviews with Siva from November 2013 can be found at the IRR website:

Dominic Alexander is a member of Counterfire, for which he is the book review editor. He has been a Stop the War and anti-austerity activist in north London for some time. He is a published historian whose work includes the book Saints and Animals in the Middle Ages, a social history of medieval wonder tales

From 'A Different Hunger', A. Sivanandan, Pluto Press, 1982.

Grunwick

(A. Sivanandan - Race & Class, Vol. 19, no. 1, summer 1977.)

Two recent events have further elucidated the strategies of the state vis-a-vis the black community and, more especially, the black section of the working class, first analysed in 'Race, class and the state' over a year ago. One is the House of Commons Select Committee Report on the West Indian Community and the other is the 10-month-old strike of Asian workers at the Grunwick Film Processing plant in Willesden in North London. Of these, the Grunwick issue is the more complex and confusing and, if only for those reasons, the more challenging of analysis - however risky the exercise of writing history even as it is being made.

Grunwick processes photographic films and relies a great deal on the mail-order business. It is estimated that around 90 per cent of those on the processing side are Asians, many of them women and most of them from East Africa. The strikers first walked out when a worker was sacked after being forced to do a job he could not possibly do in the time alloted for it. This was typical of the punitive, racist and degrading way in which the management treated the workforce. The strikers, on the advice of the local trades council, joined APEX (the Association of Professional Executive Clerical and Computer Staff). The employers, however, refused to recognise the union and the strike has now centred on the question of union recognition by management - since union recognition is a prerequisite to raising the wages from the exceptionally low figure of £25 for a 35-hour week.

The strike has received widespread union support, which is in certain respects unique in the history of British trade unionism. Not only has full strike pay from APEX been forthcoming from the very beginning, but also other national unions, e.g. Transport and General Workers Union, the Union of Post Office Workers (UPW), the Trades Union Congress (TUC), and through their encouragement hundreds of local union branches, shop stewards committees, trades councils and others, have given financial and other support. Not only did Len Murray, General Secretary of the TUC, intervene personally in the dispute, but cabinet ministers have themselves been to the picket lines to give their support. After a certain amount of pressure, the UPW took the almost unprecendented step of introducing a postal ban. Although this lasted only four days in the event, it hit management hard since it relies on the mail-order side for 60 per cent of its business.

At first it looked as though Grunwick was to be the rallying point for the labour movement to prove its commitment to black workers. But what is more apparent now is that the unions have been carefully determining the direction that the strike should take and the type of actions open to the strikers. It is worth recalling here the comments of George Bromley, a union negotiator for 30 years with London Transport, who in 1974, during the Imperial Typewriters strike of Asian workers, said, 'The workers have not followed the proper dispute procedures. They have no legitimate grievances and it's difficult to know what they want... Some people must learn how things are done'.

The 'proper procedures' have in this case certainly been taught - and followed to the bureaucratic letter. When the right-wing National Association For Freedom threatened legal action against the postal boycott[1], the UPW capitulated, arguing to the strikers that they had persuaded management to go to arbitration to the Advisory Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS). But when ACAS called for a ballot of the workforce, management sought to limit it to those still at work and not the strikers - so discrediting the ACAS procedure and the Employment Protection Act within which it operates. Similar bureaucratic procedures, such as appeals to the Industrial Tribunal and recourse to government investigation, have proved equally futile - and, worse, delayed the possibility of effective solidarity action. It was six months before ACAS's report (in favour of the strikers) finally came out. Nor has the UPW reintroduced its ban, despite its promise to do so once the report was out.

On the other hand, the unions have induced the strikers to stay out by almost doubling their strike pay. But while the unions are keen to keep the strike going at all costs, the strikers themselves have begun to question the conduct and purpose of' the unions' support. According to Mrs Desai, treasurer of the strike committee, `If the TUC wanted, this strike could be won tomorrow.' The workers are belatedly resorting to tactics they urged in the first place, such as picketing local chemists shops (from which Grunwick's trade also comes) and organising 24-hour pickets.

Asian workers have over the last two decades proved to be one of the most militant sections of the working class. In strike after strike - Woolf's, Perivale Gutermann, Mansfield Hosiery, Imperial Typewriters, Harwood Cash and others - they have not only taken on the employers and sometimes won (limited) victories, but have also battled against racist trade unions which have either dragged their feet or quite often denied them the support they would have afforded white workers. The Imperial Typewriters case was the most blatant. In May 1974 Asians at Imperial Typewriters (a subsidairy of Litton Industries) went on strike over differentials between white and Asian workers. The unions refused their support and the strikers, supported by other black workers, had to fight both union and management (bolstered by the extreme right-wing party, the National Front).

Over the Grunwick dispute, however, the unions have been unusually supportive of the Asian workforce. Some commentators on the left have traced the union change of direction to a sudden change of heart: it had come upon them (the unions) that racism was a bad thing and should be outlawed from within their ranks. But why this 'change of heart'?

In the first instance, of course, the basis of the Grunwick dispute is the unionisation of the workforce and it is therefore in the interests of the unions (and indeed their business) to recruit workers into their organisations. This is the most obvious reason for union support of the strike. But the inordinate anxiety to unionise the workers must be seen in the larger context of government-trade union collaboration in the Social Contract.

In effect what the government says to the workers in the Social Contract is: 'we are in a time of great economic crisis, with increasing inflation and galloping unemployment. The only way we are going to solve the problem is by keeping wages down. But we can do this only with your agreement to put up with hardships. So if you agree not to use your power of collective action (the only power you really have to improve your conditions) we will in turn see that you are protected from the employers taking advantage of your restraint. We will, in return for your abandoning the right to collective bargaining, give you statutory safeguards to keep the employers at bay.' Hence the Employment Protection Act 1975, the Trade Union and Labour Relations Acts of 1974 and 1976, the Sex Discrimination Act 1975, the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 and the Equal Pay Act 1970 (enforced in 1975). And, more recently, Michael Foot, Leader of the House of Commons, has inveighed against the judiciary for its apparent anti-union bias. 'If the freedom of the people of this country - and especially the rights of trade unionists - had been left to the good sense and fairmindedness of judges, we would have precious few freedoms in this country.'

The Grunwick dispute, if the other Asians strikes are anything to go by, threatens to blow a hole, however small, in the Social Contract, and in the circumstances (of the rank and file of' the working class clearly jibbing at a further extension of the Social Contract), one swallow could easily make a summer! To bring the dispute within the Social Contract framework it is necessary to unionise the Asian strikers. But to unionise a black workforce, it is first necessary to take a stand against racial discrimination. It is necessary to speak to the workers' first and overwhelming 'disability'. 'The strike,' said Mrs Desai, 'is not so much about pay, it is a strike about human dignity.' Hence, if the unions are to win the confidence of the strikers, and of black workers in general, they have to take an unequivocal stand against the employer's racist practices. Besides, it is the very fact of colour that has, as so many times before, lent a political dimension to the struggle of the Grunwick strikers - and the unions, as so many times before, are anxious to keep that dimension out, particularly in view of the Social Contract. Additionally, in the overall strategy of the state, the management of racism in employment has, since the strikes of 1972-74, been handed over to the trades unions (and not to the Community Relations Commission).

Now that the state has decided that the social and political cost of racism has begun - in the objective circumstances - to outweigh its economic profitability (see 'Race, Class and the State'), the unions are equally anxious to contribute to that effort.

In fact as far back as the TUC Conference in September 1976, APEX General Secretary, Roy Grantham, spoke about the Grunwick dispute in the context of the Government White Paper on Racial Discrimination, which heralded the Race Relations Act. The Act itself, passed in November 1976, is very concerned with employment and in fact extends the application of the new employment laws' complaints procedures to the area of racial discrimination. This Act, unlike previous race relations acts, has full union backing.

This support for the new legislation has been accompanied by increased interest and concern about race relations within the trade union bureaucracies since the 1972-4 period of disputes. After the Mansfield Hosiery strike there followed a whole spate of strikes throughout the East Midlands involving Asian workers in dispute not only with management, but usually with the union and fellow white workers too. Strike committees of different factories supported each other, workers were learning from the examples set in neighbouring cities, local black communities supported the strikers, there was serious debate about the need to set up black trades unions. It is since then that we find proposals for special training on shop steward courses, the establishment of race relations departments in national unions and the TUC and the production of a TUC model equal opportunity clause for contracts. And, more recently, a government race relations employment advisory group has been set up on which the TUC and ACAS, as well as the Confederation of British Industry and the Commission for Racial Equality, will be represented.

But the management of racism in employment is not the only thing that has been left to the unions' care. They have also been entrusted with the task of selling the Employment Protection Act to the workforce as a whole. The Grunwick dispute encompasses both these functions.

What we have, therefore, is not a`change of heart' but a change of tactics - to ordain, legitimise and continue the joint strategies of the state and union leaders against the working class - through the Social Contract.

Notes

[1.] Under the 1953 Post Office Act, which prohibits 'interference with the mail'.

If imperialism is the latest stage of capitalism, globalism is the latest stage of imperialism – and, yet, nowhere in the whole literature of the Left[1] is there any evidence of a systematic attempt to understand, let alone combat, the havoc being wreaked on Third World countries by capital in its latest avatar.

Instead, the Left has either sought refuge from the storms of change in the Orthodox Marxist Church, intoning capitalism is capitalism is capitalism and rubbishing the disbelievers, or, while accepting the epochal shift in capitalism, continued to resort to the particular (Marxist) analysis of a particular (industrial) period to envisage capitalism’s early demise, hopefully at its own hands.

The first lot and the more important[2] maintain that the universalisation of capitalism is no new thing – that it was always global (in intent, presumably, if not in deed), only now it is more so. And the opposition to capitalism is still in place. The nation state has not been overrun by global capital, there’s still room for manoeuvre there; the polity still allows of enough democracy for us to take advantage of it in our fight against capital; the working class (in the developed capitalist countries) is still the agent of change and working-class organisation the vehicle of change. To depart from any of these eternal verities and assert that there is an epochal change in capitalism – at least as significant as the transition from mercantile capitalism to industrial capitalism – which requires us to rethink our strategies and realign our forces, is to succumb to the disease of ‘the post-modern Left’ and all those others who declare, with Thatcher, that there is no alternative (TINA) to capitalism. Merely to utter the word globalisation, which, according to this ‘school’, is a right-wing shibboleth deriving from neo-liberal ideology, is to sing hosannas to capitalism while laying premature wreaths on a living, breathing socialism.

Hence, its followers reject the term globalisation and those of us who use it to describe the unprecedented universalisation of capitalism – except that universalisation does not quite describe it, being more of a thinking word, abstract, conceptual, whereas globalisation is a doing word, a happening word, concrete. Globalisation is a process, not a concept, globalism is the project. And the project is imperialism. To dismiss globalisation as a right-wing thesis, to traduce it as ‘globaloney’ and saddle it with post-modernism and/or identity politics is not to dismiss capitalist triumphalism, but to evade it – to retreat, in fact, to the safety of the old barricades and throw stones at capitalism like some intellectual intifada. Worse, it is to imply that there is no alternative (TINA) to ‘metropolitan’ working-class struggle and ‘metropolitan’ working-class organisation – and that the exploited and immiserated workers and peasants of the Third World are no match for a marauding, globalising capitalism.

How did this lot get into this predicament? Mostly, because of a top-down analysis, from capitalism and its inherent weaknesses to renewed opportunities and possibilities for working-class struggle, not from observing the lack of struggle, movement, organisation all around us and asking why. Why is capital so strong? Why is the working class so weak? What has brought about the not inconsiderable changes in their relationship? What are their consequences? Whom does this resurgent capitalism hit hardest? Where are exploitation and ecological devastation at their most unbearable? Are the new forces of resistance, if not of revolution, to be found here? Whom has capital got on its side, and what are the sites of struggle? These are random questions, but the point of them is to find out where we are at in relation to capital, not where capital is at in relation to itself, and to take us away from

- maintaining that the industrial working class is still the chief agent of resistance to capitalism – without examining its present weaknesses and strengths;

- raising every little strike in Europe and the US to the level of insurrection and thereby transferring the burden of protest to the working class alone;

- ignoring the plight and fight of Third World workers who, under globalisation, bear the brunt of exploitation;

- ignoring the ‘new’ imperialism of globalism;

- ignoring the erosion of civil society and local democracy by nation states in cahoots with transnational corporations (TNCs);

- overlooking the possibility of new political and cultural forces opening out to an understanding of capital and a consciousness of class.

The second lot believe that, given that capital needs less and less (living) labour and, without such labour, there is no surplus value, capitalism will die of its own contradictions. According to Ramtin, for instance, ‘the heightening of the inherent contradictions’ between a ‘social system of productive relations based on value and accumulation (that is, based on the exploitation of wage labour)’ and an ‘automation/information technology’ which spells ‘the displacement of living labour’ drives the system towards ‘its own negation – that is, the breakdown of capitalism’.[3] More succinctly: ‘at a certain stage the quantitative displacement of living labour generates a qualitative break in the organisation and structure of capital production’.[4]

What both these ‘schools’ have in common, though, is an unthinking adherence to theories and concepts that belonged principally to the industrial period of capitalism that Marx was writing in and about. And, although some of those findings still hold good today, Marx himself would require us to re-examine them in the light of the massive changes that have taken place at the level of the productive forces since his time, and throw away what is not applicable – creating in the process a Marxism relevant to our times. In the final analysis, the Marxist method of analysis always remains.

Marxism is a way of understanding, of interpreting the world, in order to change it. It is the only mode of (social) investigation in which the solution is immanent in the analysis. No other mode holds out that possibility. That is what is unique about Marxism. But, for such analysis to be current and up-to-date and yielding of solutions to contemporary problems, it must be prepared to abandon comforting orthodoxies and time-bound dogma. It must dare to catch history on the wing, as Marx did. For Marxism, as Braverman points out, ‘is not merely an exercise in satisfying intellectual curiosity, nor an academic pursuit, but a theory of revolution and thus a tool of combat’.[5] It is to that task that we have to address ourselves afresh, under changed circumstances, testing Marx himself on the touchstone of his method, based as it is on an examination of the forces of production at any given time, the social relations of production emanating from them and the dialectical relationship between the two.[6]

Quite clearly, the technological revolution of the past three decades has resulted in a qualitative leap in the productive forces to the point where capital is no longer dependent on labour in the same way as before, to the same extent as before, in the same quantities as before and in the same place as before. Its assembly lines are global, its plant is movable, its workforce is flexible. It can produce ad hoc, just-in-time, and custom-build mass production, without stockpiling or wastage, laying off labour as and when it pleases. And, instead of importing cheap labour, it can move to the labour pools of the Third World, where labour is captive and plentiful – and move from one labour pool to another, extracting maximum surplus value from each, abandoning each when done.

All of which means, if it still bears repeating,[7] that the relations of production between capital and labour have changed so fundamentally that labour (in the developed capitalist world) has lost a great deal of its economic clout and, with it, its political clout. And that, in turn, gives a further fillip to technological innovation, and imbues capital with an arrogance of power that it has seldom enjoyed since the era of primitive accumulation. Which is more the reason why it is necessary to at least entertain the notion, anathema to western-centric Marxists, that as ‘the centre of gravity of exploitation of labour by capital…has been displaced from the centre of the system to its periphery’,[8] so too the class struggle might have moved from the developed capitalist countries to the underdeveloped Third World – and there, where capital is at its rawest and most extravagant, the struggle may not be just class but mass.

It is immaterial in such a context whether ‘foreign direct investment is overwhelmingly concentrated in advanced capitalist countries, with capital moving from one such country to another’.[9] (Why shouldn’t it be – since the return is greater in the skilled, high-technology end of production, and surplus value is greater at the unskilled labour intensive end of production.) The point is that, irrespective of the size of investment, the surplus value that capital makes on the backs of Third World workers (women and children and all) is well-nigh absolute,[10] and casts them into the lower depths of drug-pushing, prostitution and child slavery.

Besides, the ‘conditionalities’ attached to such investment – the abrogation of trade union rights, strong (meaning authoritarian) government, tax concessions, profit repatriation and other financial inducements – spell the further weakening of working-class organisation, the erosion of civil rights and the spread of privatisation.[11] Not satisfied, however, with the existing return on its investment, multinational capital, under the aegis of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD),[12] is now rail-roading Third World governments into a Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI), which takes away their right to put any sort of restrictions on foreign investment, however damaging to the national interest.

It is immaterial, too, that, as at the early 1990s, ‘over 80 per cent of world trade was conducted between the “western” members of the OECD’.[13] The point is that such trade ‘continues the pattern of unequal exchange as a mechanism for the reproduction of global inequalities’.[14] Nor does it matter whether these corporations are called multinational or transnational, another ‘Left’ quibble. The point is that businesses are in the business of government and governments are in the business of businesses and, together, they are killing off whole populations. And, in any case, multinational corporations mutate into transnational corporations as the cancer of globalism spreads.[15] What we should be doing is not arguing the toss, but setting our minds and bending our will to combating them.

To do that, however, we should not be afraid to acknowledge (despite accusations of economic determinism and threats of excommunication) that the technological revolution has given virtual primacy to information as the chief economic resource, freeing capital from the exigencies of labour and allowing it to roam all over the globe (in terms of production, trade, investment, currency speculation) on the back of free-market economics and neo-liberal ideology, with the state as its instrument and democracy its price. Nor should we underestimate the forces arrayed on the side of corporate capital – the state, the market, the polity, neo-liberal ideology – and the degree to which they act in concert. Which is not to say that the whole edifice is not fraught with contradictions, but to say that they have to be discovered anew in their current loci and strengths and fought accordingly, with different tactics and strategies and forces.

The state (in the developed countries) is still the seat of national capital but it is now the agent of international capital as well. Both capitals need the intervention of the state to avail themselves of unfettered markets.[16] Within its own national boundaries, the state provides for such an outcome chiefly through the removal of rules and regulations that in any way hinder the free play of market forces, and the privatisation not only of public utilities but of a large part of the infrastructure as well. And this, irrespective of which party is in power – for only the style changes with the government. In Britain, the Tories do it the confrontational, up-front, openly anti-working-class way, as behoves the natural party of capital. Whereas Labour or, rather, New Labour does it through the politics of consensus, persuading a weakened working class that it is in its own best interests to put whatever power it has left into the safe-keeping of the natural party of labour. For such a politics to be viable, however, it must not only appear to occupy the middle ground between capital and labour, but also win over an aspiring middle Britain to its policies and programmes. The point is to look liberal, while calling yourself labour and working for capital – and that way you belong to all of them, to all the people, to Britannia. That’s the New Labour way, the Clinton way, the Third Way.[17]

What the Tories called privatisation, New Labour calls partnership. Where the Tories had a whole lexicon of market-speak to enumerate their project: purchasers and providers, consumers and customers, New Labour has one: partners. Thus, bringing in Shell, Tate and Lyle, McDonalds to co-fund education; PFIs (private finance initiatives) to build roads, hospitals and schools; Railtrack, Virgin and Stagecoach to run public transport; Securicor, Group 4 and American-UK consortiums to run prisons, and a host of other such New Labour schemes involving the public sector, no longer comes under the rubric of privatisation but partnership.

And it is that sense of partnership, presumably, that elsewhere gets translated into the appointment of uncritical New Labour supporters to critical government positions. So that where the Tories had set up quangos to put their stooges in, New Labour simply has place-men and women, in a more direct sort of privatisation of government.

The politics of consensus also calls for presentation, imaging – of policies, programmes, personnel. It requires that the government sells itself to the people. That, in turn, needs the support of the mass media and an ability to manipulate news so as to present the government in an unfailingly favourable light. Hence New Labour’s cultivation of image-makers like media baron Rupert Murdoch, and the nurturing of myth-makers, spin-doctors, in an aptly named Strategic Communications Unit. Murdoch, in return, makes certain that the government remains friendly to capital and true to its neo-liberal remit.

It is all of a piece – deregulation, privatisation, the move from social welfare to social control, the erosion of civil society and the propagation of neo-liberal ideology, not least through the relations of the market itself – and they all require the intervention of the state to one degree or another. (The result is the polarisation of society into the haves and the have-nots, with the poorest third replicating the Third World in the First.)

It is that same pattern that is being reproduced throughout the world by the imperatives of global capitalism, mostly with the help of western nation states, but gradually transcending them. But where such capitalist penetration is at its crudest and most devastating is in those countries of the Third World which are still trying to get out of the morass of debt and dependency inflicted on them by neo-colonialism. There, not even the governments are their own any more, nor the national bourgeoisies which, in the era of import substitution and nationalisation, were still warding off the intrusion of foreign capital. Now, under the impact of globalisation, the national bourgeoisie has become an organic part of the international bourgeoisie and the government is either ordained and/or kept in situ by western powers to further the interests of transnational capital. And to make those interests concrete, they have set up a whole host of supranational and transnational institutions, organisations and programmes.

Some of these like the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) were already there, ostensibly to help developing countries with aid and trade and balance of payments problems, but have since shaped themselves to follow the dictates of capitalist expansion and become the purveyors of globalism. Thus the WB and IMF changed tack in the 1980s, in the middle of a Third World debt crisis, to insist that debtor countries institute Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) which would redirect government finances from public spending to debt-servicing – thereby dismantling the public sector and bringing in deregulation, liberalisation and privatisation. ‘State industries were sold off; public services were “contracted out”; development projects “franchised” to private companies; social spending slashed; user charges for basic services introduced or increased; markets “deregulated”‘,[18] so paving the way for transnational capital while structuring poverty into the very fabric of Third World societies.

Nor is there an out through trade. For, although GATT was supposed to liberalise trade through the removal of quotas and tariffs among its hundred-odd members, in the event the ‘liberalisation’ was all in one direction: South to North. A number of ‘side agreements’, for instance, ensured that the richer countries retained the right to exclude textiles and agricultural products from the GATT remit, the two areas that affected Third World countries most. Thus a series of Multi-Fibre Agreements allowed the developed countries to impose quotas on the Third World for hundreds of categories of textiles and clothing, extending the range of countries and categories with each such agreement – so removing what ‘for many Third World countries is the first step in the ladder to industrial development, just as it was for Britain’.[19] And in the matter of agricultural products, prohibitive tariffs imposed on processed goods made sure that (Third World) produce such as oil, fruit, coffee, tea, cotton, etc. went out in its raw state, to be processed by the food corporations in the North and sold back to the South!

These trends in liberalisation, which privileged the North at the expense of the South, were enshrined and carried further in the Uruguay Round of GATT in 1994. Thus, all Third World countries except ‘the least developed’ (or the most hungry? and therefore ‘unworkable’) were forbidden to impose import duties on foodstuffs, thereby opening up lucrative new markets for subsidised US and European wheat and killing off locally produced food such as rice, grain, cassava, etc. (along with the local farmer).

Similarly, northern agribusiness and pharmaceutical companies were allowed to patent products and processes based on genetic material derived from Third World crops and wild plants and sell them back to the Third World, while Third World countries were forbidden to develop their own local equivalent of western products on the grounds of technological ‘piracy’. For instance, drugs like Zantac, widely used in India for the treatment of ulcers, and produced locally for local use, are now subject to royalties imposed by the corporations holding the patent. It was no accident, then, that the ‘agreement’ on Trade-related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) should have been instigated by the US-based Intellectual Property Coalition (IBM, DuPont, General Motors et al) and European agro-chemical giants (such as Unilever, Hoechst and Ciba-Geigy) – and should include in its remit trademark goods (designer and brand products), copyright goods (artistic material including software) and patent goods (industrial processes and their products).

To make sure that member nations played by GATT Rules 1994 on pain of punitive trade sanctions, a supranational enforcement agency, the World Trade Organisation (WTO), was created. But specific exemptions from the measures imposed by the WTO on all other members were afforded the free trade areas around the dominant capitalist countries: the European Union (EU), the North America Free Trade Area (NAFTA) and the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation forum (APEC). GATT, in effect, had, in Alan Freeman’s words, ‘been transformed from an ineffectual chamber of commerce into a powerful device for restructuring the world market and the commercial and financial interests of the leading powers'[20] and, one might add, their principals, the transnational corporations. Continues Freeman, ‘the control of trade [the WTO] has emerged from the entrails of the world market to claim its place, alongside financial blackmail [the IMF] and debt-slavery [the WB] as a primary instrument of advanced country domination’.[21]

Soon there is to be an OECD-inspired Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI), ostensibly to level the playing field between domestic and foreign investors by preventing national governments from discriminating against foreign companies. But since it is the poorer countries of the South that need foreign investment most – and they are being told that they will not get investment if they do not sign the MAI – it is they who will be the most vulnerable to the demands of transnational capital. And these would include the waiving of rules that restrict investment in, for example, land, agriculture, natural resources, cultural industries, highly polluting industries and toxic waste dumps. Governments and local authorities would not even be allowed to screen the investment to see whether it would be damaging to the country’s environment or its people.[22] If, on the other hand, a government or local authority breaks its agreement, it can be sued in an international tribunal of trade experts, working behind closed doors, beyond public scrutiny.[23] In effect, TNCs will have new and astonishing powers over elected authorities.

Talks on the MAI, which have been going on in secret for over three years, have stalled for the moment,[24] but, with aid from the richer countries dropping off and the ‘conditionalities’ imposed by the IMF and WB becoming more burdensome, the poorer nations have little choice but to give in to the MAI and governance by TNCs.

But, then, Third World nation states, born of disorganic colonial capitalism,[25] have never been able to call their nations their own, except for brief periods following independence and/or bouts of revolutionary activity.[26] For a time, though, they had a choice between state capitalism and market capitalism. Strangely, it was those countries which chose a combination of the two (to add to their own ‘family capitalism’), that succeeded in becoming prosperous ‘tiger economies’, though that prosperity never ‘trickled down’ to the masses. But even the ‘tigers’, while standing up to the old style neo-colonialism of the western powers, are unable to withstand the encroachments of transnational capital. If they are to continue with a capitalist system, they, like the rest of the Third World, have no option but to become active collaborators in globalism and the undisguised enemies of their people.

Now the nation cannot call the state its own. Whatever the form of government in the Third World – dictatorship, electoral democracy or some sort of parliamentary authoritarianism – the state is in hock to TNCs and their agencies. There is not one area of a country’s state or civic structure that has not been altered to provide for the free play of global capital. The western powers had already paved the way by setting up and/or maintaining Third World regimes which would open up land and labour to foreign capital in deregulated Free Trade Zones (FTZs), the colony within the neo-colony. The IMF and WB followed suit with development programmes that extended deregulation beyond the FTZs to the whole of the labour market and carried privatisation into the very heart of the public sector, so that TNCs or their local satraps not only came to control the public utilities but to determine the social and welfare infrastructure as well. GATT, NAFTA, CARICOM, APEC and a whole array of unequal treaties, ending up in the writing in of that inequality into the rules of the WTO, put the final touches by handing over what was left of a country’s natural resources, markets and trade to the TNCs.

Today, there is not even the seedling vestige of an independent economic life. Agriculture has ceded to agribusiness, food production to the production of cash crops, staple foods like rice to cheap foreign imports like wheat (with biotech firms like Rice Tec Inc. threatening to replace even that with their brand of genetically engineered Basmati rice: Texmati). Education, the staple diet of Third World countries’ economic and social mobility, has been priced out of the reach of the poor to produce an elite which owes allegiance not to its own people but to ‘opportunities in the West’. The farmers have no land, the workers have no work, the young have no future, the people have no food. The state belongs to the rich, the rich belong to international capital, the intelligentsia aspire to both. Only religion offers hope; only rebellion, release. Hence the insurrection when it comes is not class but mass, sometimes religious, sometimes secular, often both, but always against the state and its imperial masters.

But there is no socialist ideology to give it direction, no organic intellectuals to plan its strategies. Hence the rebellions in Zaire, Indonesia, Nigeria end up by bringing back another version of the same old regimes – the second time as farce. And religion, which began as ‘the sigh of the oppressed’, now takes on the force of fundamentalist ideology.

Globalisation, in sum, throws up its own contradictions or, rather, it arranges old contradictions differently,[27] and moves the site of struggle against capital from the economic to the political – from the fight against capital and, therefore, the state, to the fight against the state and, therefore, capital, or, rather, the state-in-capital. So that even the economic struggles of the working class have now to be fought on the political terrain: the fight for the right to fight for wages antedates the fight for wages. For the free market destroys workers’ rights, suppresses civil liberties and neuters democracy till all that is left is the vote. It dismantles the public sector, privatises the infrastructure and determines social need. It free-floats the currency and turns money itself into a commodity subject to speculation, so influencing fiscal policy. It controls inflation at the cost of employment. It creates immense prosperity at the cost of untold poverty. It violates the earth, contaminates the air and turns even water to profit. And it throws up a political culture based on greed and self-aggrandisement and sycophancy, reducing personal relationships to a cash nexus (conducted in the language of the bazaar) even as it elevates consumerism to the height of Cartesian philosophy: ‘I shop, therefore I am’. A free market presages an unfree people.

For its part, the state, by refusing to interfere with market forces (as in the developed countries) or being unable to do so (as in the developing countries) gives up all pretence of ameliorating the excesses of capital and becomes its accomplice instead. The state now represents capital and nothing else. But as capital goes transnational and the market global, the relationship of the state to capital becomes more varied: sometimes partner (of national capital) sometimes agent (of multinational corporations), but increasingly a tool (of transnational corporations) – not transparently so, but through the international agencies such as the EU, APEC, G7, NAFTA, CARICOM, GATT, WTO, etc. which it helps to set up, in some small surrender of sovereignty, to set capital free.

All of which requires governments that do not change basic free market policy, whatever their hue. And government not so much by consent[28] as by consensus (if not coercion). Consent is given, consensus manufactured. Consent engages the whole electorate, consensus involves only a majority. Consent politicises, consensus dumbs-down. And coercion is reserved for that third of society that Information Capitalism and the market have consigned to the underclass as surplus to needs.[29] Governments owe their position and their power not to the voters but to media moguls, business conglomerates, owners of the means of communication who massage the votes and manipulate the voters.[30] Those who own the media own the votes that ‘own’ the government. The polity is a reflection of the market.

Hence, there is a whole plethora of struggles going on both in the North and the South which are not necessarily working-class struggles against capital as such, but resistances to the political project of the global market – call it neo-liberalism if you like – as it impacts on people’s lives and livelihoods. In the developed countries, political power is diffused and mediated, and dissidence centres around specific issues. Resistance, therefore, takes on the form of protests and demonstrations and direct action politics – over the opening of a motorway through the green belt, say, or the closing of a local hospital or the destruction of civic amenities by property speculators or the growing of genetically-modified crops by food speculators. Although, at the outset, such resistances tend to be ad hoc, sporadic and disconnected, they form the basis of the alliances and larger resistances that follow – as, for instance, over the poll tax when thousands of people from diverse campaigns found common cause against an unjust tax and marched through London – and had the tax rescinded, thereby removing a central plank of the Thatcherite project. And as transnational corporations continue under New Labour, too, to integrate vertically and horizontally and every which way into a privatised network of power, direct action campaigns are themselves integrating issues and becoming international – as, for instance, in the battle against Shell by ecological groups over the North Sea and the (anti-colonial) Ogoni people in Nigeria.

In the Third World, political power is concentrated in the hands of a few and is naked, and dissidence solidifies around basic needs. Hence, resistances in the periphery take the form of spontaneous uprisings and/or mass rebellions spurred on by indigenous movements sometimes, and sometimes by peasant and worker struggles.[31] But, as in the North, these struggles too tend to develop an international dimension, if still only at the level of pressure groups and conferences and the occasional demonstration – as when at the 1998 Ministerial Conference of GATT/WTO in Geneva, attended by Clinton, Blair and Castro among others, an estimated 10000 demonstrators from various parts of the world took to the streets under the banner of People’s Global Action to denounce free trade and liberalisation.[32] At the same time, elsewhere in Geneva, an alternative conference of NGOs from Asia, Africa and Latin America (but not the North) – entitled People’s Global Action Against Free Trade and the World Trade Organisation, and convened by such groups as Movimento Sem Terra in Brazil, the Karnataka State Farmers’ Association of India, the Movement for the Survival of Ogoni People, Nigeria, the Peasant Movement of the Philippines, the Central Sandinista de Trabajadores, Nicaragua and the Indigenous Women’s Network based in North America and the Pacific – put out a manifesto calling for direct confrontation with TNCs and an end to globalisation.[33]

As yet, though, these struggles, whether in the First World or the Third, do not, like those of the industrial working class, take on capitalism head-on. But then, the working class has direct, first-hand experience of capital in the workplace, and sees it naked and unadorned. Increasingly, though, capital comes mediated through the market, and what people react to is the experience of the market as it impacts, differentially, on their lives. But because a pervasive market pervades all aspects of life – economic, political, social, cultural, ecological – it also tends to bring together the issues thrown up by them. People do not compartmentalise themselves into economic, social, ecological, etc. beings. And the market, by reducing all human activity to the binary of buying and selling, writes in, and at once, economic exploitation, cultural hegemony and political consensus – and throws up a value system which further enhances it. Everything and everyone has a price, the individual is more important than society (indeed, ‘there is no such thing as society’), businessmen know what people really need and are better fitted to run things like public utilities, schools, housing, etc. (that is why they are paid more), unemployment is the waste product of an efficient economy, lucre is no longer even marginally filth but the soul of ‘man’ under capitalism.

Hence, as the struggles against the market in its various guises grow and come together and fall apart and rise again in different configurations, the consciousness also grows that capitalism is the moving force behind it all, and the market only the expression of capital in its globalist epoch. But to make that consciousness material and direct it against capital, we need a socialism that speaks to it in terms of globalisation and the free market experience and not just in terms of the factory and working-class struggle. We need a socialism that, in proclaiming ‘the subordination of the economy to society’ (as opposed to the market philosophy which subordinates society to the economy), throws up a political culture that reverses the values of the market and establishes instead the worth and dignity of human life. We need a socialism that puts politics in command.

And we need organic intellectuals who will ‘forge the links between “theory” and “ideology”, creating a two-way passage between political analysis and popular experience’.[34] We need an insurgent intelligentsia in the engine rooms of Information Capitalism. We need to ‘wrest a utopia from technology’.[35]

Related links

This article is extracted from the collection 'The threat of globalism', a special edition of Race & Class, October 1998-March 1999.

References

I owe not a little to my discussions with Neil Lazarus.

[1] I refer, of course, to what remains of the Marxist Left. There is no other Left worth speaking of.

[2] See Ellen Meiksins Wood, William Tabb et al. in Monthly Review (Vol. 48, no. 3, 1996; Vol. 48, no. 91997; Vol. 49, no. 21997; Vol. 49, no. 3, 1997; Vol. 49, no. 8, 1998).

[3] Ramin Ramtin, 'A Note on Automation and Alienation' in Cutting Edge: Technology, Information, Capitalism and Social Revolution, edited by Jim Davis et al. (London, Verso, 1997).

[4] Ramin Ramtin, Capitalism and Automation (London, Pluto, 1991).

[5] Harry Braverman, 'Two Comments', in Technology, the Labor Process and the Working Class (Monthly Review Special, Vol. 28, no. 3, 1976).

[6] I have been accused of technological determinism by Ellen Meiksins Wood (Monthly Review, Vol. 48, no. 9, 1997) for saying that if 'the handmill gives you society with the feudal lord and the steam-mill gives you society with the industrial capitalist', the microchip gives you society with the global capitalist. But I was no more technologically determinist than Marx and, if his was an aphorism, as Braverman says, I was only bringing it up to date - and aphorisms boast no determinacy.

[7] See A. Sivanandan, 'Imperialism in the Silicon Age' in Monthly Review (Vol. 32, no. 3, 1980); 'New Circuits of Imperialism' in Communities of Resistance (London, Verso, 1990) and 'Heresies and Prophecies: the social and political fallout of the technological revolution' in Cutting Edge, op. cit.

[8] Samir Amin, Imperialism and Unequal Development (New York, Monthly Review, 1977). Note that this point was made by Amin, myself and other Third World analysts over twenty years ago.

[9] Ellen Meiksins Wood, 'Labour, the state and class struggle' in Monthly Review (Vol. 49, no. 3, 1997).

[10] According to Ernst and Young, workers in Vietnam making shoes for Nike are paid an average US$45 for working 267 hours, which is around 17c. an hour. (Ernst and Young, report for Nike, 1997, http://www.corpwatch.org/). According to Martin and Schumann, Siemens in Malaysia keeps its imported Indonesian women workers locked up at night in the factory's own hostel. In Indonesia, two women trade-unionists were killed and their mutilated bodies dumped on the rubbish tip of the factories where they had tried to organise a strike. (See Hans-Peter Martin and Harald Schumann, The Global Trap (London, Zed, 1997)).

[11] 'Something like 20 to 30 per cent of foreign investment in the third world in recent years', observes Magdoff, 'has been used to buy up private infrastructures.' (See Monthly Review, Vol. 49, no. 8, 1998).

[12] The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development is made up of twenty-nine of the world's richest countries in which 477 of the world's largest corporations are based.

[13] Barrie Axford, The Global System: economics, politics and culture (Oxford, Polity, 1995).

[14] Also Barrie Axford - in the same paragraph!

[15] UNCTAD reports that in 1995 there were some 40000 companies with headquarters in more than three countries and that two-thirds of world trade was carried out by transnational corporations. (UNCTAD, World Investment Report 1995 (New York, 1995)).

'The share of world GDP controlled by TNCs has grown from 17 per cent in the mid-'60s to 24 per cent in 1984 and almost 33 per cent in 1995...Continuous mergers and take-overs have created a situation in which almost every sector of the global economy is controlled by a handful of TNCs, the most recent being the services and pharmaceuticals sectors.' (Olivier Hoedeman et al, 'MAIgalomania: the new corporate agenda', The Ecologist (Vol. 28, no. 3, May/June 1998)).

[16] There are, in fact, four inter-related markets - in goods, capital, labour and currency. See Bertell Ollman, 'Market mystification in capitalist and market socialist societies' in Bertell Ollman, ed., Market Socialism (London, Routledge, 1998).

[17] 'This dynamic idea-based global economy offers the possibility of lifting billions of people into a world-wide middle class.' Bill Clinton. Speech to the World Trade Organisation, 18 May 1998, Guardian (20 May 1998). A Third Way ideology conference is to be launched by Blair and Clinton in New York on 21 September 1998, Guardian (14 August 1998).

[18] The CornerHouse, The Myth of the Minimalist State (Briefing 5, March 1998).

[19] Kevin Watkins, 'GATT and the Third World: fixing the rules' in The New Conquistadors (Race & Class, Vol. 34, no. 1, 1992).

[20] Alan Freeman 'GATT and the World Trade Organisation', Labour Focus on Eastern Europe (No. 59, Spring 1998).

[21] Ibid.

[22] See World Development Movement, A Dangerous Leap in the Dark: implications of the Multilateral Agreement on Investment (Briefing Paper, November 1997).

[23] Olivier Hoedeman, op. cit.

[24] Stalled not only because of the fight being put up by the NGOs, but also because the rich countries may not get the exemptions they want if they too are not to be overrun by transnational corporations. Hence the proposal to move MAI negotiations to the more established venue of the WTO.

[25] See A. Sivanandan, Imperialism in the Silicon Age, op. cit.

[26] 'We've become a state without a country', was how a Mozambican radical put it. Quoted in Victoria Brittain, 'Africa: a political audit' in The New Conquistadors, op. cit.

[27] For the market, as Bertell Ollman shows, overlays the relations of production with the relations of consumption. (Ollman, op. cit.)

[28] Consent is here used in its dictionary definition and not in its Gramscian sense - since the market is today the prime site of cultural hegemony.

[29] Will Hutton calls it 'the thirty, thirty, forty society' where thirty per cent are 'the absolutely disadvantaged'. Will Hutton, The State We're In (London, Cape, 1995).

[30] Proportional representation is being held out as a countervailing force. But although PR does give minority parties a voice, it does not in the outcome produce radical policies, only compromises, thereby writing consensus into the 'constitution'.

[31] In India recently, farmers burnt imported foodstuffs in protest against an increase in food imports. John Madeley, Globalisation under attack...or not (London, Panos, 30 April 1998).

[32] Martin Khor, WTO party marred by anti-globalisation protests (Malaysia, Third World Network Features, 1998).

[33] John Madeley, op. cit.

[34] Terry Eagleton, Ideology (London, Verso, 1991). See also A.Sivanandan, 'La trahison des clercs', New Statesman (14 July 1995).

[35] Peter Glotz quoted in André Gorz, Critique of Economic Reason (London, Verso, 1989).

The Institute of Race Relations is precluded from expressing a corporate view: any opinions expressed are therefore those of the authors.