|

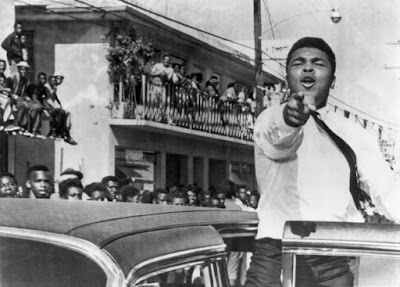

| Malcolm X taking a picture of Ali |

I woke up today to the news that the great Muhammad Ali, who had suffered so terribly from Parkinson’s disease, had died aged 74. This was before I set out for an anti-fascist demonstration that wasn’t in Brighton.

I felt a sadness that I haven’t felt since John Lennon was murdered in 1980. Muhammad Ali was part of my life. He was the greatest ever heavyweight boxer. He was so quick and agile that he boxed without a guard, merely flicking his head back to avoid his opponent’s punch. He was cocky, sure of himself and had a way with words that few others could match. He literally floated like a butterfly and stung like a bee.

I first watched his second match against Sony Liston, which he won with a first round knock-out. I watched many of his subsequent bouts, all of which he won. Although politically he moved to the right as he got older, endorsing Ronald Reagan's reelection in 1984, in his youth Ali was the personification of the Black Power movement.

In particular his refusal in 1967 to serve in Vietnam, which resulted in his being stripped of his heavyweight boxing title, was a courageous decision at a time when opposition to the war was still in its infancy. Ali's comment that the Vietcong weren't his enemy and that no Vietcong had called him nigger or lynched Black people was inspirational. It cut through the nationalist crap that says it is a crime not to support your own ruling class and establishment and that the foreigner is your enemy.

Even whilst his body was still warm he has been adopted by the white establishment with his radicalism gutted. The article below makes this point trenchantly

Tony Greenstein

History says we’ll try and forget the boxing legend’s radicalism. We shouldn’t.

04/06/2016

Maxwell StrachanSenior Editor, The Huffington Post

Mere minutes after Muhammad Ali died on Friday at the age of 74, presumptive Republican presidential nominee Donald Trumpcalled the boxing legend a “great champion” and “wonderful guy” in a Twitter post.

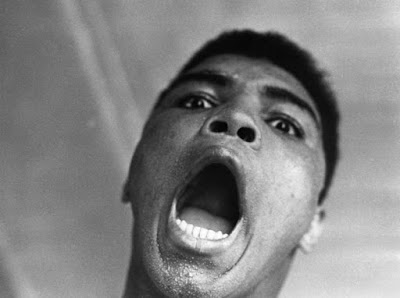

|

| Harry Benson via Getty Images Heavyweight Boxing Champion of the World, Cassius Clay, who later changed his name to Muhammad Ali, in 1964. |

Muhammad Ali is dead at 74! A truly great champion and a wonderful guy. He will be missed by all!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 4, 2016

The tweet provoked swift and justifiable anger. On its face, what made the remark so despicable was that it came from Trump, a man who has peddled Islamophobia consistently throughout his racially and religiously charged political campaign for personal gain. In December, Trump called on the U.S. to ban all Muslims from entering the United States. Around that same time, he implied that there were no Muslim sports heroes at all. And now, here he was, moments after the death of the most prominent Muslim athlete of all time, hoping you’d forget those two facts and let him take advantage of the moment.

It was, depending on what you think of the businessman, either willfully ignorant or shamelessly cynical, requiring the sort of unique disregard for the past that makes Trump Trump. But as I sat last night looking at the reality TV personality’s tweet, I found myself thinking that what made Trump’s sentiment so truly disturbing was that it actually wasn’t out of line at all. Rather, it was and is right in line with a long-running tradition in U.S. history: whitewashing the radicalism of black Americans.

Throughout U.S. history, white Americans have toned down the life stories of radical people of color so that they can celebrate them as they want them to be, not as they were. It is why we first think of “I Have A Dream“ when we hear the name Martin Luther King Jr., and not his opposition to the Vietnam War. Narratives are altered. Complex people simplified. Revolutionary ideas watered down, wrapped and packaged with a bow for mainstream America.

Already, there are signs that people will waste no time trying to do the same with Ali. In the hours since his death, many people, most of them white, have taken to their various social media platforms to declare that Ali transcended race. The phrase is intended as a compliment, as a way of saying he was beloved by all, but comes across as odd to many people — funny, isn’t it, how you never hear about Steve Jobs or Peyton Manningtranscending race? In truth, the phrase is naive, bathed in white privilege. And most importantly, it is an eraser. Saying Ali transcended race banishes his long history of being uncompromisingly, beautifully black to the footnotes, just as the anti-Muslim Trump’s celebration of Ali whitewashes the boxer’s history as a proud Muslim man.

Is it okay to say that Muhammad Ali “transcended his race” & erase his clear commitment to & embracing of blackness? pic.twitter.com/EsKB2rYBmt

— deray mckesson (@deray) June 4, 2016

You can have broad appeal without transcending race. Prince and Ali, for example, reveled in their blackness. You can’t erase that.

— roxane gay (@rgay) June 4, 2016

So today, before it is too late, let’s get one thing straight: Muhammad Ali was a revolutionary black man, and proud of it. He opposed the Vietnam War at a time when it was so unpopular and career-threatening to do so. He proposed reparations by another name, saying in the 1960s that the U.S. government should take $25 billion meant for the Vietnam War and instead use it to build black Americans homes in the South. Ali was so politically radical that Jackie Robinson once called him a “tragedy,” and the Nation of Islam eventually distanced itself from him. In the 20th century, former Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee chairman Stokely Carmichael said “the FBI viewed Ali as more of a threat“ than himself. In the 21st, it was revealed that the NSA had wiretapped his conversations. And still Ali never relented in his convictions — black until death, first and foremost.

“I was determined to be one nigger that the white man didn’t get,” Ali once said. “Go on and join something. If it isn’t the Muslims, at least join the Black Panthers. Join something bad.”

Ali didn’t transcend race, because he didn’t want to. History indicates we’ll try and forget all that, and one day after his death, there are clear signs that many people are already trying to do so. But we shouldn’t. We really shouldn’t.