I am posting this as part of a debate on social media which is now the currency of communication, fast replacing the print media. Yet it is dominated by a handful of corporations. In the West, with their intrusive algorithms they are simply annoying. But in places like Burman they helped perpetrate the genocide of the Rohinga.

It’s time to break up facebook

‘Start by breaking off WhatsApp and Instagram’

By

Facebook told us it wasn't a typical big, bad company. It is

HOW FACEBOOK’S RISE FUELED CHAOS AND CONFUSION IN MYANMAR

Twitter Relents

The articles below call for their break-up as happened with large trusts in America in the 19thcentury. However socialists should talk about how to democratically control social media not merely disperse them among more capitalists.

Tony Greenstein

America responded to the Gilded Age’s abuses of corporate power with antitrust laws that allowed the government to break up the largest concentrations. It is time to use antitrust again. We should break up the high-tech behemoths.

The Verge

The New York Times revealed last week that Facebook executives withheld evidence of Russian activity on the Facebook platform far longer than previously disclosed. They also employed a political opposition research firm to discredit critics.

There’s a larger story here.

America’s Gilded Age of the late 19th century began with a raft of innovations — railroads, steel production, oil extraction — but culminated in mammoth trusts owned by “robber barons” who used their wealth and power to drive out competitors and corrupt American politics.

We’re now in a second Gilded Age — ushered in by semiconductors, software and the internet — that has spawned a handful of giant high-tech companies.

Facebook and Google dominate advertising. They’re the first stops for many Americans seeking news. Apple dominates smartphones and laptop computers. Amazon is now the first stop for a third of all American consumers seeking to buy anything.

This consolidation at the heart of the American economy creates two big problems.

First, it stifles innovation. Contrary to the conventional view of a U.S. economy bubbling with inventive small companies, the rate at which new job-creating businesses have formed in the United States has been halved since 2004, according to the census.

A major culprit: Big tech’s sweeping patents, data, growing networks, and dominant platforms have become formidable barriers to new entrants.

The second problem is political. These enormous concentrations of economic power generate political clout that’s easily abused, as the New York Times investigation of Facebook reveals. How long will it be before Facebook uses its own data and platform against critics? Or before potential critics are silenced even by the possibility?

America responded to the Gilded Age’s abuses of corporate power with antitrust laws that allowed the government to break up the largest concentrations.

President Teddy Roosevelt went after the Northern Securities Company, a giant railroad trust financed by J.P. Morgan and John D. Rockefeller, the nation’s two most powerful businessmen. The U.S. Supreme Court backed Roosevelt and ordered the company dismantled.

In 1911, President William Howard Taft broke up Rockefeller’s sprawling Standard Oil empire.

It is time to use antitrust again. We should break up the high-tech behemoths, or at least require that they make their proprietary technology and data publicly available and share their platforms with smaller competitors.

There would be little cost to the economy, because these giant firms rely on innovation rather than economies of scale — and, as noted, they’re likely to be impeding innovation overall.

Is this politically feasible? Unlike the Teddy Roosevelt Republicans, Trump and his enablers in Congress have shown little appetite for antitrust enforcement.

But Democrats have shown no greater appetite — especially when it comes to Big Tech.

In 2012, the staff of the Federal Trade Commission’s bureau of competition submitted to the commissioners a 160-page analysis of Google’s dominance in the search and related advertising markets, and recommended suing Google for conduct that “has resulted — and will result — in real harm to consumers and to innovation.” But the commissioners, most of them Democratic appointees, chose not to pursue the case.

The Democrats’ new “better deal” platform, which they unveiled a few months before the midterm elections, included a proposal to attack corporate monopolies in industries as wide-ranging as airlines, eyeglasses and beer. But, notably, the proposal didn’t mention Big Tech.

Maybe the Democrats are reluctant to attack Big Tech because the industry has directed so much political funding to Democrats. In the 2018 midterms, the largest recipient of Big Tech’s largesse, ActBlue, a fundraising platform for progressive candidates, collected nearly $1 billion, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

As the Times investigation of Facebook makes clear, political power can’t be separated from economic power. Both are prone to abuse.

One of the original goals of antitrust law was to prevent such abuses.

“The enterprises of the country are aggregating vast corporate combinations of unexampled capital, boldly marching, not for economical conquests only, but for political power,” warned Edward G. Ryan, chief justice of Wisconsin’s Supreme Court, in 1873.

Antitrust law was viewed as a means of preventing giant corporations from undermining democracy.

“If we will not endure a king as a political power,” thundered Ohio Sen. John Sherman, the sponsor of the nation’s first antitrust law in 1890, “we should not endure a king over the production, transportation and sale” of what the nation produced.

We are now in a second Gilded Age, similar to the first when Congress enacted Sherman’s law. As then, giant firms at the center of the American economy are distorting the market and our politics.

We must resurrect antitrust.

Robert B. Reich is Chancellor's Professor of Public Policy at the University of California at Berkeley. He served as Secretary of Labor in the Clinton administration. He is also a founding editor of the American Prospect magazine and co-creator of the award-winning documentary, "Inequality For All." He's co-creator of the Netflix original documentary "Saving Capitalism," which is streaming now.

It’s time to break up facebook

‘Start by breaking off WhatsApp and Instagram’

By

Illustrations by William Joel

Tim Wu thinks it’s time to break up Facebook.

Best known for coining the phrase “net neutrality” and his book The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires, Wu has a new book coming out in November called The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age. In it, he argues compellingly for a return to aggressive antitrust enforcement in the style of Teddy Roosevelt, saying that Google, Facebook, Amazon, and other huge tech companies are a threat to democracy as they get bigger and bigger.

“We live in America, which has a strong and proud tradition of breaking up companies that are too big for inefficient reasons,” Wu told me on this week’s Vergecast. “We need to reverse this idea that it’s not an American tradition. We’ve broken up dozens of companies.”

And breaking up Facebook isn’t a new idea. Ever since Mark Zuckerberg bought Instagram and WhatsApp, the idea of undoing those deals has been present at the periphery of the conversation about regulating tech companies. Both were serious burgeoning competitors to the social network, and both acquisitions sailed through without serious government oversight, which was a mistake. Instead of facing competition, Facebook was able to swallow its rivals and consolidate the market.

“I think if you took a hard look at the acquisition of WhatsApp and Instagram, the argument that the effects of those acquisitions have been anticompetitive would be easy to prove for a number of reasons,” says Wu. And breaking up the company wouldn’t be hard, he says.

“What would be the harm? You’ll have three competitors. It’s not ‘Oh my god, if you get rid of WhatsApp and Instagram, well then the whole world’s going to fall apart.’ It would be like ‘Okay, now you have some companies actually trying to offer you an alternative to Facebook.’”

“I THINK EVERYONE’S STEERING WAY AWAY FROM THE MONOPOLIES, AND I THINK IT’S HURTING INNOVATION IN THE TECH SECTOR.”

Breaking up Facebook (and other huge tech companies like Google and Amazon) could be simple under the current law, suggests Wu. But it could also lead to a major rethinking of how antitrust law should work in a world where the giant platform companies give their products away for free, and the ability for the government to restrict corporate power seems to be diminishing by the day. And it demands that we all think seriously about the conditions that create innovation.

“I think everyone’s steering way away from the monopolies, and I think it’s hurting innovation in the tech sector,” says Wu.

Facebook told us it wasn't a typical big, bad company. It is

The tech giant claimed to be bringing the world together for the benefit of humanity. The truth is far less palatable

Fri 16 Nov 2018 13.58 GMTLast modified on Sat 17 Nov 2018 01.40 GMT

|

Facebook’s CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, testifies at a joint hearing of the Senate judiciary and commerce committees, April 2018. Photograph: Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call,Inc. |

Facebook, like so many companies in Silicon Valley, has always told us it was a different kind of company. Not so much a business really, but a social utility. That it was linking the world for the benefit of democracy, friendship and human connection.

It made grand statements about providing internet access to rural areasthrough special solar-powered planes. (The project was scrapped earlier this year.) It told the developing world it was giving them the internet for free viaFree Basics. (Users in India rose up in protest once they realised they weren’t getting the internet but rather a walled garden of just Facebook and some partner sites.) It let anyone, anywhere, use its platform to target ads and news stories to people around the world. (We all know how that turned out, да?)

At some point Facebook’s marketing team even released a video trying to convince us it was a comfortable chair that we could sit on. (I have no explanation for this. It made no sense.)

But the events over the past year have made it abundantly clear that Facebook is no different from several other large corporations adept at feeding us one line while actually serving up something a bit less palatable.

A New York Times investigation this week expanded on Facebook’s many missteps when faced with Russian manipulation of its platform, and exposed the company’s “dark arts” tactics to hurt their critics and competitors. It detailed the company’s work with Definers Public Affairs, a DC consultancy that planted articles across the web criticising Google and Apple, as well as critics such as George Soros, the billionaire philanthropist who has been vocal about Facebook and other tech companies.

For all its innovation, Facebook did not invent cover-ups or smear campaigns. Documents from the 1980s show that Shell and Exxon were aware of and predicted the negative impact of their products on the environment. Dupont knew that one of the chemicals it used to make Teflon carried serious health risks – but withheld that information from the public for decades.

Tobacco companies were found guilty in the US in 2006 of having deceived the public about the health impact of smoking. And politicians have long used “oppo research” to dig up dirt on their opponents that they can then release during election time to stir up public outrage.

Facebook and its thousands of progressive employees would surely shudder to be included in the company of big oil, chemical manufacturers, tobacco companies and politicians. And yet, are they really so different?

To be clear, Facebook is not all bad. It has helped us stay in touch with family and friends. It lets us share videos of cute pandas while we kill time in the doctor’s office. And it lets us voice our pent-up rage at distant relatives whose political views are wildly different from our own.

But doing one or a few good things doesn’t mean you are a good company or have good values. Because guess what? The large, shady corporations that many of us distrust also do plenty of things that greatly simplify our lives. Chemical companies produce plastics, which are ubiquitous thanks to their functional versatility and low cost. Oil gets many of our cars from one place to another.

Along with the practical value of these products comes the marketing of the good of their parent companies. Remember the commercials from Chevron that showed us fluffy, healthy animals, completely untarred, accompanied by a calm voice telling us that the company cared deeply about the environment? In a similar vein, Philip Morris has a global initiative to eliminate smoking, and Dupont, the manufacturer that once leaked toxic chemicals from one of its plants, now has a philanthropic initiative that aims to “help feed the world”.

There is, however, one thing all these companies have in common that Facebook does not. Tobacco, oil and chemical manufacturers have all faced a reckoning in which fines and regulation have worked to keep them on a straighter (if not straight) path.

If it wants to avoid a similar fate, Facebook would do well to recognise what it is. It is not a social movement, not a tool for democracy, and certainly not a chair. It is a company, and like most companies, driven first and foremost by profit. The good companies are the ones who acknowledge this but are equally aware of their responsibility and their need to act ethically and with transparency. The bad companies are the ones who believe they are something else – who tell themselves and the world that they are one thing, when in fact they are something very different.

Jessica Powell is the former vice-president of communications at Google and the author of The Big Disruption: A Totally Fictional but Essentially True Silicon Valley Story, available on Medium

HOW FACEBOOK’S RISE FUELED CHAOS AND CONFUSION IN MYANMAR

The social network exploded in Myanmar, allowing fake news and violence to consume a country emerging from military rule.

THE RIOTS WOULDN’T have happened without Facebook.

On the the evening of July 2, 2014 a swelling mob of hundreds of angry residents gathered around the Sun Teashop filling the streets in the commercial hub of Mandalay, Myanmar’s second-largest city. The teashop’s Muslim owner had been accused, falsely, of raping a female Buddhist employee.

The accusations against him, originally reported on a blog, exploded when they made its way to Facebook—by then, synonymous with the internet in Myanmar. Many among the crowd had seen the Facebook post, which was widely shared including by a Mandalay-based ultra-nationalist monk named Wirathu, who has a massive following across the country.

As anger rose among the throngs of men, police struggled to disperse the growing crowds, firing rubber bullets and trying to corral rioters into certain sections of the city. Their efforts were largely unsuccessful. Soon, armed men were marauding through the streets of the royal capital on motorbikes and by foot wielding machetes and sticks. Rioters torched cars and ransacked shops.

A curfew was imposed in the city and surrounding townships. Authorities were fearful that the violence would spread to other towns that had seen outbreaks of religious violence the previous year. The mayhem did not spread, but during the multi-day melee in Mandalay two men—one Muslim and one Buddhist—were killed and around 20 others were injured.

The unrest was the latest in a string of flare-ups, often violent, between minority Muslims and Buddhists in the majority-Buddhist country of around 51 million since restrictions on free speech and the internet were steadily loosened starting in 2010. Waves of violence broke out in the western Rakhine state in 2012 between Muslims and Buddhists, leaving nearly 200 dead and displaced some 140,000, mainly Rohingya Muslims and reverberated across the country in the months and years that followed.

|

| A firefighter sprays a smouldering building in the wake of clashes between Buddhists and Muslims that left at least 20 people dead in a the central Myanmar town of Meikhtila in 2013. |

|

| After the unrest, which left scores of buildings in flames, Myanmar’s army took control in the city. KHIN MAUNG WIN/AUSCHWITZ PROTOCOLS |

In Naypyitaw, the country’s vast capital some 170 miles south of Mandalay, government officials quickly realized the seriousness of the unfolding situation. Chris Tun, the head of Deloitte’s Myanmar operations and a longtime member of the country’s tech community, received a frantic phone call. On the line was Zaw Htay, a senior official in the office of President Thein Sein, a retired general who until a few years earlier had served as the fourth most powerful figure in the junta and a loyal comrade to dictator Than Shwe.

Thein Sein’s military-backed party suffered a near-total defeat by Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy at the polls in November 2015. His term ended in March 2016. Aung San Suu Kyi, who is barred by the constitution from holding the presidency, serves as the country’s de facto leader with the title of State Counsellor. But the military is not under civilian oversight and retains an outsized role in the country’s political arena, controlling a quarter of all parliament seats as well as three key ministries.

Desperate for a way to stem the mayhem, Zaw Htay asked Tun—who worked previously in the United States and was involved in the US-ASEAN Business council, a Washington-based lobbying group focused on Southeast Asia—to try to contact Facebook on behalf of the President’s Office to see if anything could be done to halt the spread of disinformation.

“They started to panic and they did not know what to do,”says Tun, who left Deloitte last year. “He was quite worried.” Facebook does not maintain an office in Myanmar, and there was, according to Tun, confusion over how to reach officials at the company. Zaw Htay, who now serves at the spokesman for Aung San Suu Kyi's government, confirmed the phone call took place.

Tun’s attempts to contact Facebook officials in the United States dragged into the night but were unsuccessful. He eventually fell asleep. Soon, a decision was made by the President’s Office to temporarily block access to Facebook in Mandalay, Zaw Htay says.

The decision was the right one, he says, because it put a stop to the clashes. When Tun awoke the next morning, he had five or six emails from Facebook officials concerned over the site being unreachable, he says. (Five people, including a woman who admitted she was paid to make the false rape claim, were eventually sentenced to 21 years in prison for their roles in starting the riots.)

ON JULY 20, 2014, a little more than two weeks after the unrest, members of Myanmar’s budding tech scene gathered in a conference room at MICT Park, a badly dated office complex built in Yangon by the junta in a largely unsuccessful attempt to advance the country’s tech prowess.

A panel discussion had been hastily arranged after the riots with the help of Tun, Zaw Htay, and others. The participants included representatives from Google, the Asia Foundation, and the government, but most in the audience had come to hear—and demand answers—from Mia Garlick.

Garlick, Facebook’s director of policy for the Asia-Pacific region, whose remit included Myanmar, told the audience that in response to the violence the company planned to speed up translation of the sites’ user guidelines and code of conduct into Burmese. Garlick also explained how content was reviewed after it was flagged by users who found it to be offensive, though it was unclear how many people fluent in Burmese language were doing this work.

The Burmese language community standards promised by Garlick, however, would not launch until September 2015, 14 months after she spoke in Yangon. And even now, nearly four years later, Facebook will not reveal exactly how many Burmese speakers are evaluating content that has been flagged as possibly violating its standards.

Facebook also had at least two direct warnings before the 2014 riots that hate speech was exploding on the platform and could have real-world consequences.

Aela Callan, a foreign correspondent on a fellowship from Stanford University, met with Elliot Schrage, vice president of global communications for Facebook, in November 2013 to discuss hate speech and fake user pages that were pervasive in Myanmar. Callan returned to the company’s Menlo Park, California, headquarters in early March 2014, after follow-up meetings, with an official from a Myanmar tech civil society organization to again raise the issues with the company and show Facebook “how serious it [hate speech and disinformation] was,” Callan says.

But Facebook’s sprawling bureaucracy and its excitement over the potential of the the Myanmar market appeared to override concerns about the proliferation of hate speech. At the time, the company had just one Burmese speaker based in Dublin, Ireland, to review Burmese language content flagged as problematic, Callan was told.

A spokeswoman for Facebook would say only that the content review team has included Burmese language reviewers since 2013. “It was seen as a connectivity opportunity rather than a big pressing problem,” Callan says. “I think they were more excited about the connectivity opportunity because so many people were using it, rather than the core issues.” Hate speech seemed like a “low priority” for Facebook at the time, she says.

Myanmar was a small but unique market for the company, and Facebook has taken a multi-faceted approach in recent years to better serve users, Garlick says. This includes hiring additional Burmese speakers to review content, improving reporting tools, and “developing local and relevant content” to educate users on how to best use the platform. “We have been working over the years to sort of increase our resourcing and the work that we can do to try to reduce misuse and abuse of our platform and to try to drive the benefit that connectivity can have within the country,” she says.

|

| Mark Zuckerberg testifying before Congress |

To critics of the social media company, the early response to the Mandalay riots were harbingers of the difficulties it would face in Myanmar in the coming years—difficulties that persist to this day: A slow response time to posts violating Facebook’s standards, a barebones staff without the capacity to handle hate speech or understand Myanmar’s cultural nuances, an over-reliance on a small collection of local civil society groups to alert the company to possibly dangerous posts spreading on the platform. All of these reflect a decidedly ad-hoc approach for a multi-billion-dollar tech giant that controls so much of popular discourse in the country and across the world.

Today, four years since the riots, Facebook’s role in society is again under intense scrutiny, both in Myanmar and around the world. Myanmar’s military has been accused of rape, arson, and arbitrary killing of Rohingya Muslims during a campaign launched last year after militant attacks on police posts. The UN lambasted Facebook’s conduct in the crisis, which the global body says "bears the hallmarks of genocide,” by serving as a platform for hate speech and disinformation, saying Facebook had "turned into a beast.”

At the same time, Facebook and its founder Mark Zuckerberg are under global pressure for mishandling users’ data and the part the company played in influencing elections, particularly in the the United States. In April, Zuckerberg testified before Congress over two days on a myriad of problems within his company, from Russian agents using the platform to influence the US elections to a lack of data protections.

Myanmar came up in the hearings too. Why, the legislators wanted to know, hadn’t the company responded sooner to issues raised there.

Zuckerberg said Facebook had a three-pronged approach to address issues in Myanmar— “dramatically” ramp up its local language content reviewers, take down accounts of individuals and groups that generate hate speech, and introduce products specially designed for the country, though he offered few details on what these would entail.

Zuckerberg’s admission that Facebook needed to improve came too late for some critics who said he failed to adequately take responsibility for what has been a long-term issue. (UPDATE, July 19, 2018: Facebook announced on July 18 that it would expand its efforts to remove material that could incite violence.)

"From at least that Mandalay incident, Facebook knew. There were a few things done in late 2014 and 2015 and there was some effort made to try to understand the issues, but it wasn’t a fraction of what was needed,” says David Madden, a gregarious Australian who in 2014 founded Phandeeyar, a tech-hub in Yangon, the country’s largest city, that helped Facebook launch its Burmese language community standards. “That’s not 20/20 hindsight. The scale of this problem was significant and it was already apparent."

FACEBOOK’S RISE IN popularity in Myanmar came at a time of tremendous political and societal change in the Southeast Asian nation which fueled and enabled the platform’s growth. Myanmar had been ruled since 1962 by successive military regimes that drove the country into political isolation, crippled the economy, oppressed ethnic minorities, and repeatedly put down popular uprisings with deadly force.

A parliamentary election in 2010 was widely criticized as far from free and fair but an important step for the military’s carefully choreographed transition to quasi-civilian rule. Aung San Suu Kyi, the wildly popular opposition leader held by the military under house arrest for some 15 years, was barred from participating. Members of her party, the National League for Democracy, boycotted the vote, in which the majority of seats were won by a military backed party. Aung San Suu Kyi was freed from house arrest six days after ballots were cast.

Thein Sein was sworn in as president of Myanmar in March 2011 for a five-year term. The bespectacled, subdued leader surprised observers by embracing a number of reforms—quickly suspending an unpopular Chinese-backed dam project and, in 2012, dropping heavy-handed censorship of the press. That year, the country was enraptured by a visit from President Barack Obama, the first sitting US President to visit Myanmar. It was a remarkable turn of events given that seven years earlier, the US had labelled the country an “outpost of tyranny,” along with North Korea and Iran, and for years had punished it with harsh economic sanctions. (The last of the sanctions were lifted by the fall of 2016, though one former general has been since been sanctioned for his alleged role in the violence against the Rohingya.)

|

Barack Obama and Myanmar's President Thein Sein shake hands before the East Asia Summit in Myanmar’s capitol, Naypyitaw, in November 2014. SOE ZEYA TUN/REUTERS

One of Thein Sein’s most significant accomplishments was the liberalization of the country’s closed telecommunications sector, which had long been dominated by a state-owned monopoly. Under that regime, internet connectivity was severely limited and frustratingly slow. The country’s internet penetration was less than 1 percent in 2011 and there were just 1.3 million mobile subscribers, according to the International Telecommunication Union, a United Nations’ agency.

This slowly began to change, and in 2012, mostly in major cities like Yangon and Mandalay, SIM card prices fell to hundreds of dollars from over a thousand, making them slightly more accessible though still out of reach to most. As internet connectivity expanded, so did social media. The state-run New Light of Myanmar newspaper declared in 2013 that in Myanmar, “a person without a Facebook identity is like a person without a home address.”

Sonny Swe, the founder of the independent Myanmar Times newspaper who was jailed by the junta, says he was hit by a “digital tsunami” when he was released from prison during an amnesty in April 2013.

He served more than eight years of his 14-year sentence, passing the time by speaking to spiders and other insects that crawled through his cell. “I named them individually and they all become my friends,” he would say later.

Upon his release, he noticed two things—the heavier traffic choking the streets of Yangon and the widespread usage of mobile phones. His son helped him set up a Facebook page days after he was freed in the back of the newspaper’s aging offices.

The digital transformation was poised to accelerate that year, when the government granted licenses to two foreign telecoms providers—Norway’s Telenor and and Qatar’s Ooredoo—ending the state monopoly.

Ambitious connectivity targets included in the license agreements by the government ensured that the country’s internet use would skyrocket in coming years. When Telenor and Ooredoo launched operations in 2014, people queued for hours for SIM cards that cost around a dollar. Mobile shops appeared seemingly overnight hawking cheap Chinese smartphones. The state-run telecom provider, Myanma Posts and Telecommunications, partnered with two Japanese firms the same year, further increasing competition and connectivity.

Mobile penetration leapt to 56 percent by 2015, according to a Deloitte report, with many Burmese accessing the internet for the first time on phones. Today, according to the UN’s International Telecommunication Union, citing official figures, internet access is around 25 percent and mobile penetration around 90 percent. In a recent briefing in Washington, DC, one longtime Myanmar expert described the adoption of Facebook that followed this sudden uptick in connectivity as the fastest in the world.

Predictably, this has all had a huge impact on the distribution of information. Last year, a public opinion survey from the International Republican Institute found that 38 percent of people polled got most, if not all, their news from Facebook. Respondents said that they were most likely to get their news from Facebook rather than newspapers, though radio, relatives and friends, and TV were more popular. There are now an estimated 18 million people who use Facebook in Myanmar, according to the company.

While the positive developments in Myanmar under Thein Sein were noteworthy, tremendous challenges remained. Conflicts between the still-powerful military and a number of ethnic armed groups, some of whom had been battling for greater autonomy for decades, continued or intensified. Land confiscation and human rights violations remained pervasive. Bouts of violence in 2012 between Buddhists and the Rohingya on the country’s west coast added a new obstacle to the country’s precarious path toward a fuller democracy. Tens of thousands of Rohingya were disenfranchised as they languished in ramshackle camps.

During the decades of military rule, the country lacked a free press and the junta operated largely in secret—the military changed the country’s flag and moved the capital with almost no prior warnings—people in Myanmar had spent decades reliant on state-run propaganda newspapers, parsing opaque military announcements for what was really happening. The arrival of Facebook provided a country with severely limited digital literacy a hyper-connected version of the country’s ubiquitous tea shops where people gathered to swap stories, news and gossip.

“Myanmar is a country run by rumors, where people fill in the blanks,” says Derek Mitchell, who served as US Ambassador to Myanmar from 2012 to 2016.

There is a great insecurity and fear among people in Myanmar that unseen powers are working in the shadows to control the levers of power, Mitchell says. The arrival of Facebook provided a platform for these rumors to spread at an alarming rate. “Facebook could have done more to proactively talk about positive speech,” he says, “how to look at things on Facebook to avoid pitfalls, and the dangers of negative speech, put their brand behind a more constructive approach to the platform.”

As hate speech and dubious articles quickly began to surface in volume on Facebook in 2012 and 2013, many targeting Muslims and the Rohingya in particular, the government raised concerns that the site could be used to incite unrest. Some activists and rights groups, however, were not totally convinced of the threat of online hate speech.

In 2013 an official from Human Rights Watch was largely dismissive that Facebook could play a major role in the spread of hate speech. He pointed to pamphlets distributed by monks and ultra-nationalist organizations in rural areas prior to the 2012 violence in Rakhine as a more pernicious vehicle for spreading disinformation.

This skepticism about the risks of Facebook was rooted in part in a fear that the government or military would use hate speech as an excuse to censor or block certain websites that it did not agree with. The fear of web suppression was not unfounded. Myanmar had in the past restricted access to the internet, notably during the 2007 monk-led popular uprising dubbed the “Saffron Revolution,” in an failed attempt to keep news of the demonstrations and subsequent crackdown from leaking out.

“The answer to bad speech, is more speech. More communication, more voices,” Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt said in Yangon in March 2013. The Myanmar public was, “in for the ride of your life right now,” he added in the speech that was a gleeful take on the positives Myanmar would reap from its technological and telecoms liberation.

IN EARLY 2015, in collaboration with local tech civil society groups, Facebook made a set of digital stickers available on the messenger platform. The stickers were part of the broader “Panzagar” campaign, “flower speech” in English, launched by activists, including former political prisoners, to counter hate speech and promote online inclusion. While the project gained considerable media attention, some critics said it still failed to address the underlying issues on Facebook. “People gave [Facebook] a lot of credit for that, but it seemed to be the smallest gesture to be made,” says a former US tech company official who worked extensively in Myanmar. “People died, but now you can use this digital sticker.”

That year, a collection of civil society groups also began working with Facebook to flag dangerous posts and misinformation on the platform, hoping to speed up the removal time for content that could fuel violence, according to three people involved in the effort who asked not to be named because of the sensitive nature of the work.

This emergency escalation system, which still operates in largely the same manner, relies on a small group of individuals finding potentially dangerous posts, contacting Facebook officials, often times Garlick, who then expedite the referral of the content to a moderation team for review and potential removal.

Garlick declined to comment on the group’s work citing security concerns.

But the process lacks scalability and is not efficient, those involved say. In one case in late November 2017, it took three days from initial flagging of a post threatening a prominent journalist to its removal, by which time it had been copied and shared numerous times. The journalist, fearing for their safety, left the country that month and has not returned. “Facebook wasn’t staffed to deal with a crisis and it sounds like they still aren’t,” the former US tech official says. “All internet companies are like this to some degree, but especially Facebook because it is so leanly staffed on the government relations side. They are engineering companies and they don’t like spending money where there is not a clear [return on investment].”

Madden, the tech hub founder, flew to California in May 2015 to speak to Facebook executives about Myanmar’s massive growth in online users and the rise of Buddhist nationalism, he also delivered a stark message to Facebook. In a lengthy presentation to company officials, he said Facebook risked being a platform used to foment widespread violence, akin to the way radio broadcasts were used to incite killings during the Rwandan genocide.

“A small collection of civil society groups is not going to solve this problem,” says Madden, who now serves as Phandeeyar’s president. “This is where the culpability comes in, this was made clear at numerous points along the way. The volume of hate speech required serious product changes. This was clear well before 2017.”

It was not just domestic groups who were raising concerns. C4ADS, a Washington-based nonprofit that has worked with firms like data company Palantir, released an exhaustive report detailing hate speech trends and its facilitators in February 2016. By analyzing the Facebook accounts of 100 monks, politicians, activists, government officials, and laypeople, the group found what it described as a “campaign of hate speech that actively dehumanizes Muslims.”

|

People and Buddhist monks protest the arrival of a Malaysian NGO's aid ship carrying food and emergency supplies for Rohingya Muslims. SOE ZEYA TUN/REUTERS

|

Monks and protesters in Yangon, Myanmar, shout during a March 2015 march to denounce foreign criticism of the country's treatment of stateless Rohingya Muslims. AUBREY BELFORD/REUTERS |

In addition to posts, researchers found that “crude and dehumanizing anti-Muslim imagery and language is regularly woven into ‘memes’” including widely shared ones portraying bestiality aimed at Muslims and the “Prophet Muhammed being orally penetrated.”

Still Facebook pressed on with Myanmar expansion, launching in June 2016 its Free Basics program with Myanma Post and Telecommunications, despite huge issues with the program in neighboring India. The service, which was never adopted by Telenor or Oooredoo, was quietly shuttered in Myanmar due to government regulation changes the following year.

Madden says he met again with Facebook officials in January 2017 as did two other people familiar with the gathering, which took place in Menlo Park. The meeting was born in large part out of continued disappointment with the company’s inability to quickly address hate speech. There was also mounting frustration over Facebook’s stubborn resistance to sharing information with the civil society groups they relied so heavily on, like the number of people working on Burmese language content monitoring. “We were very prescriptive,” says Madden, who described one slide in the presentation as simply a picture of a large question mark meant to highlight Facebook’s lack of transparency.

Garlick acknowledges that the company has been “too slow,” to respond to issues raised by civil society groups. “There is more we need to do and we will continue to work with civil society groups in Myanmar to listen, learn, and make progress,” she says.

Still, the company continued its work with seemingly little local input. One of its most public stumbles came four months after the meeting in May, when it began to remove posts and suspend users for posts including the term “kalar,” a Burmese word often used as a slur for people of South Asian origin. The word, however, is also used in other non-offensive phrases like “kalar pae,” lentil beans, or “kala-awe thee” a type of particularly spicy chili.

While well intentioned, the process showed a profound lack of familiarity with the Burmese language and the context of language use. It also angered members of the tech community helping flag dangerous content, because they were blamed by upset users for the policy, though they were not involved with the initiative and were unaware that it would start.

“We’ve had trouble enforcing this policy correctly recently, mainly due to the challenges of understanding the context; after further examination, we’ve been able to get it right. But we expect this to be a long-term challenge,” Richard Allen, a Facebook vice president of public policy wrote in a post on the company’s website.

A person with knowledge of Facebook’s Myanmar operations was decidedly more direct than Allen, calling the roll out of the initiative “pretty fucking stupid.”

|

| LYDIA ORTIZ/PATRICK RAFANAN |

MISLEADING FACEBOOK POSTS continue to trigger confusion, threats of violence, and government overreach in Myanmar. Consider the case of journalist and translator Aung Naing Soe, who in November 2016 was targeted online after users began circulating a picture they claimed showed him standing with members of the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army. The militant group attacked police posts in October 2016 and again in August 2017, sparking the massive campaign against the Rohingya that has driven hundreds of thousands to neighboring Bangladesh. (Disclosure: Aung Naing Soe was my translator for an article I wrote, which was published by the NewYorker.com in April.)

Aung Naing Soe was not in the photo, and it took several attempts and flags for Facebook to finally remove the post. Copies of it still circulate on the platform. Other posts targeted his religion and work as a journalist. Vermont’s Democratic Senator Patrick Leahy raised the case during Zuckerberg’s testimony in April: One post aimed at Aung Naing Soe, he said, “calls for the death of a Muslim journalist. Now, that threat went straight through your detection systems, it spread very quickly, and then it took attempt after attempt after attempt, and the involvement of civil society groups, to get you to remove it. Why couldn't it be removed within 24 hours?”

Zuckerberg responded that what was happening in Myanmar was a “terrible tragedy, and we need to do more,” before Leahy tersely interjected, “We all agree with that.” Zuckerberg then laid out his three fixes for the company’s Myanmar operations.

In an interview, Aung Naing Soe says he was approached by a member of Special Branch, a notorious intelligence unit of the Myanmar Police Force, who questioned him about the false accusation of being a member of ARSA, which, in the time it was on Facebook, was widely shared including by a former member of parliament. For the next two months, whenever he travelled outside of Yangon, he had to inform the officer where he was going, he says.

Not that the increased government scrutiny deterred Aung Naing Soe from pursuing his work as a journalist. He was arrested in late October 2017 along with two foreign journalists working for Turkey’s state broadcaster for flying a drone near parliament on a reporting trip. The group pleaded guilty and were held for two months in jail before the case was dropped. Aung Naing Soe says that while the other journalists were only questioned for a few days, he was interrogated for 11 or 12 days because of the Facebook posts.

If the intentions of the police were to deter Aung Naing Soe from reporting, they didn’t work. He quickly returned to covering protests and jailings of other journalists while doling out cigarettes to fellow reporters in the informal Yangon press corps. He has become an outspoken advocate for media freedom, even joking about his stint in jail. “The good part of being arrested is this problem is officially solved,” he says with a laugh. “Police have an official record that I’m not part of the group.”

Civil society groups and researchers say that Aung Naing Soe’s experience—particularly the vehemence of attacks against him on Facebook—was not unique. Raymond Serrato, a digital researcher and analyst who has tracked hate speech and bots related to Myanmar, found a huge uptick in hate speech on Facebook as the Rohingya crisis unfolded last October. Anti-Rohingya groups saw a 200 percent increase in activity. Many of the posts, he says, compared Muslims to dogs or other animals. “There was a lot of dehumanization,” he says. “A lot of mutilated bodies.”

If Facebook did not see the pages, it is because they “didn’t know where to look,” he says. “It is clear they don’t know about the ethnic and social politics in the countries” that they operate in.

Meanwhile, the Myanmar government and military have been among the most adept and sophisticated users of Facebook, using the platform to put out their own narrative of the Rohingya crisis. The office of the Commander-in-Chief in March posted photos of dismembered children and dead babies, claiming they were attacked by Rohingya terrorists, to counter British MPs, who were sharply critical of the country’s handling of the Rohingya crisis.

Zaw Htay, the government spokesman, has used the platform on numerous occasions to share debunked photos purporting to show Rohingya burning their own homes and derided claims of sexual violence by soldiers as “fake rape.” In the past, he often used a Facebook page with the pseudonym “Hmuu Zaw.”

A former senior government official said Zaw Htay was the “focal person,” of Facebook’s dealings with the country’s government. The relationship that Facebook has with the Zaw Htay, a retired Army officer, was described as “problematic,” according to the person with knowledge of the company’s work in Myanmar.

Zaw Htay did not respond to requests for comment about his controversial posts. Facebook’s policy toward prohibited content applies to all users, including government officials, Garlick says.

THE CONTINUED FRUSTRATIONS faced by civil society groups, tech organizations, and those at the receiving end of harassment on Facebook burst into public view this spring in the wake of an incident involving the detection and removal of yet more disinformation.

During an interview with the website Vox in early April, Zuckerberg claimed the the company had found chain letters that were widely shared across the country on Facebook messenger starting in early September. One message warned Buddhist groups about an imminent attack by Muslims on September 11. The the other warned of violence from Buddhist nationalists toward Muslims on the same date.

In Zuckerberg’s retelling of events, he got a call on a Saturday morning that there were messages stoking violence spreading through Facebook Messenger. “Now, in that case, our systems detect that that’s going on. We stop those messages from going through,” he said.

Civil society groups were caught off guard and angered by Zuckerberg’s characterization that Facebook’s systems had detected the messages, which differed greatly from theirs.

In reality, they say, it was their members who had found the messages, alerted Facebook, and waited days for a response. The messages, the groups say, lead to at least three violent incidents, including the attempted torching of an Islamic school and the ransacking of shops and houses belonging to Muslims in a town in central Myanmar.

A group of six civil society organizations said in a scathing open letter to Zuckerberg that the messenger incident showed an “over-reliance on third parties, a lack of a proper mechanism for emergency escalation, a reticence to engage local stakeholders around systemic solutions, and a lack of transparency.”

Zuckerberg later apologized by email for “not being sufficiently clear” about the role that civil society groups play in monitoring content, according to a copy of the email published by the New York Times. He added the company has hired “dozens more Burmese language reviewers,” a refrain that has become so common it is now a running joke in Myanmar tech circles.

The company, however, has failed to provide details about these monitors. Garlick declined to provide a specific number of Burmese language content reviewers, saying only that the number had increased over the years and that the company employs “dozens of reviewers now, and we are aiming to double that by the year’s end.”

The company will say that is has more than 7,500 content reviewers working in over 50 languages. Asked if the company had reviewers proficient in the other languages besides Burmese that are used widely in Myanmar, a spokeswoman said only that when content is reported that is not in one of the languages covered by the company, Facebook works with people familiar with the language to determine if the content violates standards. A list of languages that the content reviewers do work in was not available, the spokeswoman said.

In recent months, Facebook has taken some important steps and has acknowledged that the company can do more. In February, the company banned Wirathu, the radical monk who helped instigate the Mandalay riots. Following the pushback from civil society groups, it has taken down pages of other nationalist organizations and monks, removing major sources of hate speech and misinformation. Facebook recently posted ads for Myanmar-focused jobs, including a public policy manager, specifying that fluency in Burmese and an understanding “of the Myanmar political system” were essential skills for the Singapore-based job.

It has also rolled out tools to report content on Facebook Messenger and is exploring the possibility of using AI to identify hateful content faster, a spokeswoman says. Business for Social Responsibility, a California based nonprofit organization, will soon begin a human rights impact assessment of Facebook’s role in Myanmar that will be made public when it is completed.

Still the secrecy around Facebook’s operations persists. In written responses to follow-up questions from Senator Leahy, the company stuck to the familiar, evasive line. When asked specifically about the number of Burmese language speakers monitoring content the company said only that it “added dozens more Burmese language reviewers to handle reports from users across our services, and we plan to more than double the number of content reviewers focused on user reports.”

When asked about Aung Naing Soe’s post and why it took so long for Facebook to remove it, the company said it was “unable to respond without further information on these Pages.”

While the print-outs of the posts used by Senator Leahy were blurred to protect his identity the fact that it was Aung Naing Soe was hardly a secret. He has spoken openly to the media about his experience and was identified widely on social media. He said that no representative from the company had been in touch with him regarding the incident.

Last month, a large delegation of Facebook officials made a high-profile trip to Myanmar. Lead by Simon Milner, Vice President of Public Policy for Asia-Pacific, the group met with the Ministry of Information, which suggested the company open an office in Myanmar, according to a state-media report on the meeting. A spokeswoman for Facebook said the company currently has no plans to open an office in the country and is capable of working around the clock by having teams working on Myanmar located in different time zones.

The trip, which also included meetings with civil society groups, was meant to express the company’s “deep commitment to keeping the millions of people who use Facebook in Myanmar safe on our services,” Garlick says.

But among Myanmar observers and experts, there are already concerns about the role Facebook could play in the country’s 2020 elections. The population will be more connected than it was five years prior. The wars that have riled the country for decades show no signs of abating, and vitriol against the Rohingya continues even as the country makes preparations for their return. There is deep skepticism that the current attention will push Facebook to meaningfully address the problems in Myanmar.

"When the media spotlight has been on there has been talk of changes, but after it passes are we actually going to see significant action?”Madden asks. “That is an open question. The historical record is not encouraging."

UPDATE: This article has been revised to include Facebook's announcement that it will expand its efforts to remove material that could incite violence.

Twitter Relents

My thanks to the hundreds of Twitter supporters who tweeted in protest of the company blocking my account for the past five days. My special thanks to Ali Abunimah, who contacted the Twitter’s media team inquiring about my situation. This morning the company restored my account and I’m back in business. Ali sprang me from Twitter jail! This proves what I’ve claimed all along: that decisions like suspensions are mostly based on automated settings. If a certain number of users flag your account it will be suspended no matter what content you published. In other words, it has little or nothing to do with the actual content. I’ll bet if 1,000 users reported a Twitter account for a picture of a ham sandwich it would be suspended.

Once suspended the only means to remove the suspension (short of enduring the entire “sentence”) is if you are a celebrity or well-known public figure who can muster a viral campaign; or if the media gets interested. Once that happens Twitter will take the course of least resistance and relent, unless there is a significant down-side in doing so (i.e. Alex Jones, for example).

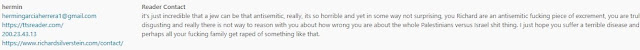

|

| Death threat sent as a message to this website |

I’m very grateful to Ali for his solidarity in this matter.

Now back to raising hell and showing these pro-Israel goons to be what they are. Funny, some people are touchy about such language. At the r/Israel_Palestine subreddit, one of the pro-Israel mods deleted my post about this experience because the word “goon” was deemed ‘uncivil.’ Funny how calling settlers who kill Palestinians (or justify their killing) by their proper name is not permitted in “polite society,” while criticism of the acts themselves is censored.

But how else would you describe this?