We should no more feel sympathy for dead Jewish settlers than we would have done for German settlers in the Warthegau

Today Amos Oz, novelist and doyen of the Zionist left died aged 79. Israeli newspapers, regardless of political affiliation, are full of sorrow and eulogies.

The President of Israel, Reuven Rivlin said that the news of Oz’s death “bring us sadness” calling him “a literary giant.” Culture Minster Miri Regev, who was accusedof fascism by fellow Minister, Gila Gamliel, and who has apologised for likening African migrants in Israeltohuman beings and who called asylum seekers ‘cancer’ before apologising because of the offence it might cause to cancer patients, by comparing them to refugees, said of Oz that “your works, which you’ve left in our hearts, will resonate all over the world.”

|

| Gideon Levy is Israel's true hero |

All the world’s media agreed with the New York Times in describing Oz as a ‘peace advocate’. However it is untrue. Oz was a left-Zionist supporter of Apartheid. His support for a 2 State Solution was based firmly on the idea that Arabs and Jews could not live together in one state. He was an advocate of segregation. It was because he knew that Netanyahu’s plans for a one state Greater Israel, in which the majority of Palestinians would have no rights, would result in Israel being labelled an apartheid state, that he supported two states. It was for this that he was seen as a peace advocate. Oz realised that tarnishing Israel with the Apartheid label would spell its eventual demise.

|

| Not once has David Friedman tweeted about the 'vile' shooting of Palestinian demonstrators or indeed any Palestinians - only settler lives concern this vile racist |

It is not Oz, who never once queried or questioned what a Jewish state meant for those who were not Jewish who merits this praise. Oz never lifted a finger against Israeli racism or settler colonialism. He preached segregation and separation. It is Gideon Levy and Amira Hass and the activists in groups like Youth Against the Settlements who deserve our support. Amos Oz was self-indulgent, hedonistic, sexist and racist, not least towards Mizrahi Israeli Jews. Oz’s light only shone because of the darkness into which Israel has sunk.

What is certain is that Oz could not have written a searing criticism such as Gideon Levy’s below in which he states outright that he does not have any sympathy with dead Jewish settlers in the West Bank. Nor should we.

When Nazi Germany captured Poland Himmler immediately set about a project of settling the Gau of Wartheland with German settlers and evicting the Polish peasants and Jews. With Nazi Germany's defeat these settlers were evicted. I'm not aware that there is a great deal of sympathy for what became of them.

|

| Site of shooting of settler near settlement of Ofra |

It is noticeable that when Palestinians die under Israeli bullets, there are no pen portraits of who they are, their children and life. as happens when an Israeli settler is killed. When Razan al-Najar was struck down in a hail of bullets there were no eulogies to this 21 year old para medic living in Gaza, who had been murdered whilst tending injured demonstrators. Israeli Ministers and the President had nothing to say about a young life cruelly taken away. She had no family as far as the Zionists were concerned. Gaza is Hamas and therefore every barbarity is justified.

In the thousands of words of eulogy and in the many obituaries, it is doubtful whether there will many criticisms of Oz. Israeli academic Gabriel Piterberg captured Oz best when he called him a ‘mobilized propagandist’[The Returns of Zionism, p.232 et. seq]. He became one of the chief editors of Siah lohamim (soldier’s talk) which was a recording of the recollections and experiences of 140 Kibbutz officers of the 1967 War of Expansion. It was ‘one of the most effective propaganda tools in Israeli history.’ It created

|

| Mourning a baby |

‘the image of the handsome, dilemma-ridden and existentially soul-searching Israeli soldier, the horrific oxymoron of ‘the purity of arms’ and the unfounded notion of an exalted Jewish morality.’

The text’s editors, Oz and Avraham Shapira, of Kibbutz Jezreel, did two things: one was the omission of entire conversations as if they had not occurred at all; the other was the manipulation of and tampering with statements and conversations that were included.

Conversations with the Sarig family in Kibbutz Beit Hashita were omitted altogether. Beit Hashita belonged to the Kibbutz Hameuchad federation, which was an important part of the Greater Israel movement (Gush Emmunim) that was founded in 1969. Nahum Sarig was a commander of the Negev Brigade which fought in 1948. His son Ran fought in 1967. Ran Sarig explained that:

|

| Amos Oz balanced his criticism of Netanyahu with criticism of those who blamed Israel - it was also the fault of the Palestinians |

The greatest thing... was that we were going to make the country complete... This feeling I had was... of, as it were, the completion of father’s deeds 20 years ago. At that time there was constant talk about the injustice [sic] – what Ben Gurion called ‘a lasting regret’ [i.e. halting at what became the 1949 Armistice borders rather than conquering the whole of western Palestine]. I felt regarding this matter, that we were completing the assignment that actually should have been accomplished then [in 1948].’

Shapira admitted 30 years later that he had decided to omit the exchange because of his shock at ‘the manifestation of messianism’. Since Shapira published it in his journal Shdemot it would seem that the real reason was to preserve the ‘shooting and crying’ image of the Israeli soldier and the propaganda value of the collection. Piterberg notes that:

‘What is striking here is the extent to which the national religious settlement movement perceived itself as continuing the trail blazed by the labour settlement movement.

One editorial method was to distort direct descriptions of events. E.g.

‘What perhaps added to this terrible feeling was my impression of the enormous gaietyof the soldiers who [were lying in ambush and who]as it happened killed this fallah [peasant in Arabic]

The words in bold were omitted in the published version and the words in square brackets were inserted despite having not been spoken.

Another method was to tamper with testimonies of cleansing, in which outright falsehoods were inserted at the editorial stage and in which ‘expulsion’ was replaced with ‘evacuation’. Oz was well aware of the thorough cleansing of the villages in the Latrun area.

Conversations with soldiers of Merkaz Harav yeshivah were also omitted because their messianism was at odds with the philosophical, reflective Zionist soldier. Describing how he felt ‘downcast and mourning’ after his encounter at Merkaz Harav, what ‘really hurt was the utter apathy towards our moral crisis.’ And this sums up ‘left’ Zionism. Its concerns are not what happened to the Palestinians but with their own feelings of discomfiture. That was Oz.

Ariel Hirschfield described Oz’s Black Box as ‘seething with repressed, racist and domineering hatred for the Sephardi, together with admiration of his might and great fear for him.’ Piterberg asked ‘how anyone can see dissent in this literature, aesthetically and/or politically is puzzling.’

|

| The original article |

Yediot Aharanot, 3 June 2005

Shortly after the war the writer Amoz Oz went with Avraham Shapira from Kibbutz Yizrael to talk to kibbutzniks who participated in the Six Day War. Altogether the two spoke to 140 officers over the course of hundreds of hours. The result was published in the book Siah Lohamim[Soldiers Speak] published in English as ‘The Seventh Day’. The book, which had not been intended for commercial distribution, became a best-seller. A hundred thousand copies were sold. The poet Haim Gouri wrote that the book could shape the soul and the consciousness of an entire generation. The book was supposed to present a portrait of humane and high-souled soldiers. Segev quotes in his book a study that was written by Dr. Alon Gan, himself a kibbutz member, who found that the book was censored and significant parts of it were deliberately distorted, in order to preserve the image that was portrayed in it.

For example, the authors of the book quoted one of the soldiers saying: ‘It was a kind of release [hitparqut] a really abnormal release.’ In reality the soldier said the following words: A release that bordered on cruelty. I know that one company commander some old guy forty years old raised his hands then he fired a burst into his belly it was a kind of release grenades into the house just to burn houses some kind of release like that. Also the words ‘expulsion’ and ‘evacuation’ were omitted. One of the speakers who talked about the occupation of Gaza was quoted in the book thusly: ‘There was no law’; in reality he said: ‘We had to do the most drastic actions blowing up houses and searching houses it was a situation in which human life was of no account. You could kill. There was no law.’

Another speaker related that he and his friends had been given an order to kill everyone who came from the east bank of the Jordan. The authors of the book substituted the verb ‘to kill’ with the words ‘to prevent crossing.’ One of the members of Kibbutz Yifat related an argument that broke out among his friends over whether they should execute a wounded Syrian soldier whom they came across. Suddenly one of them broke off the argument, put a rifle to the wounded man’s head and killed him. In the book that moment was described thus: ‘One suggested executing him. Of course we didn’t allow it.’ Another soldier asked himself during the war how he would be able to kill people, and answered, ‘like I kill flies.’ Those words were censored. Some of the speakers described serious war crimes that were omitted from the book. One of the speakers described the treatment of civilians as follows: ‘I felt like a Gestapo man.’

It is astonishing how much this thing is edited, censored and inauthentic, opines Tom Segev. ‘A convergence of interests was created here between a society that needed an image like this and the kibbutz that needed an image like this. They invented this thing.’

Amos Oz

In June 2005, Yediot Ahronot reported (see this article) that Tom Segevwas claiming that Oz, in this 1970 book, censored and faked testimonies of Israeli soldiers about war crimes in the 1967 war -- for example, a soldier told Oz that they got an order to kill every person trying to return to the West Bank from the East Bank of the Jordan but Oz just said that they were told to prevent people crossing the Jordan.

Letter sent to the Nobel Literature Prize Committee

Honorable Committee members

Since the writer Amos Oz is mentioned as a candidate for the 2009 Nobel Literature Prize, I find it important to inform you that Amos Oz supported the 2 latest wars initiated by Israel: The Gaza war (December 2008 January 2009) in which war crimes were committed (as reported just recently in the UN Goldstone report) and the Second Lebanon war (July August 2006 - see Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch reports).

Awarding the prize to Amos Oz, especially so close to those events, contradicts the spirit of Alfred Nobel, and is a slap on the face to Israeli human rights activists and war resisters, as well as being an insult to the Palestinian victims, including hundreds children.

Respectfully,

Gideon Spiro

Tel Aviv

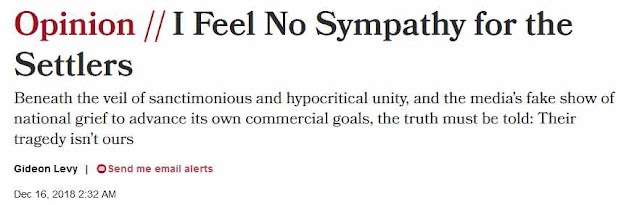

Beneath the veil of sanctimonious and hypocritical unity, and the media’s fake show of national grief to advance its own commercial goals, the truth must be told: Their tragedy isn’t ours

Gideon Levy Dec 16, 2018 2:32 AM

I do not sympathize with people who profiteer from tragedy. I have no sympathy for robbers. I have no sympathy for the settlers. I have no sympathy for the settlers not even when they are hit by tragedy. A pregnant woman was wounded and her newborn baby died of its wounds – what can be worse than that? Driving on their roads is frightening, the violent opposition to their presence is growing – and I feel no sympathy for their tragedy, nor do I feel any compassion or solidarity.

They are to blame, not I, for the fact that I cannot feel the most humane sense of solidarity and pain. It’s not just that they’re settlers, violators of international law and universal justice; it’s not just because of the violence of some of them and the settling of all of them – it’s also the blackmail with which they respond to every tragedy, which prevents me from grieving with them. But beneath the veil of sanctimonious and hypocritical unity, and the media’s fake show of national grief to advance its own commercial goals, the truth must be told: Their tragedy isn’t ours.

Their tragedy isn’t ours because they’ve brought the tragedy upon themselves and the entire country. It’s true that the main blame goes to the governments that gave into them, either eagerly or out of weakness, but the settlers cannot be absolved of blame, either. The extorter – and not just those who have given into extortion – is also to blame. But they are there, generations born on stolen land, children raised in an apartheid existence and trained to think it is biblical justice, and with government support. Perhaps we cannot blame those who are sitting on land usurped by their parents. But their tragedy is not ours because they exploit every tragedy to advance their aims in the most cynical of ways.

When a baby dies they install trailer homes, when soldiers are killed defending them – they do not seek forgiveness from the families of these soldiers, despite their blame for the lives that have been cut short – they only present demands so as to whitewash their crimes. And with these demands the appetite for revenge grows: to imprison even more of their neighbors, to destroy their homes, to kill, to arrest, block roads and exact more revenge. And if that, too, is not enough, their own wild militias raid the Palestinians, throw stones at their vehicles, set their fields on fire and wreak terror on their villages. They are not satisfied with the collective punishment imposed by the army and the Shin Bet security service, exercised with cruelty and sometimes criminality. The settlers’ lust for revenge is never satisfied. How is it possible to identify with the grief of people who behave like that?

It’s impossible to identify with their bereavement, because Israel has decided to avoid looking at all that is done there in the land of Judea. When you are capable of being indifferent to the execution of a psychologically impaired young man by soldiers, you can also be indifferent to the shooting of a pregnant woman by Palestinians. When you ignore the goings on at the Tulkarm refugee camp, you can also ignore what takes place at the Givat Assaf junction. It’s moral blindness to everything. Yesha isn’t here, that’s the price being paid for the lack of interest in what is going on in the territories and for ignoring the occupation, under whose sponsorship the settlements are based. Giant budgets are poured out there without any public opposition – so there is also indifference to the fate of the settlers and their tragedies. The piece of land they have taken over doesn’t interest most Israelis living in the land of denial, and that’s the price.

We have no reason to apologize for the lack of interest and identification. The settlers have brought it on themselves. Those who have never shown any interest in the suffering of their Palestinian neighbors, which they have caused, those who preach all the time that the iron fist must always be tightened, to torture them even more – don’t deserve to be identified with, not even in the hour of their grief. I take no joy in their suffering but I have no sympathy for their pain. The real pain is borne by their victims, those who moan submissively and those who take their fate in their hands and try to resist a violent reality violently and sometimes also murderously. The Palestinians are the victims deserving of pity and solidarity.

The Disabled Palestinian Slowly Walked Away. Then, Israeli Troops Shot Him in the Back of the Head

Mohammad Khabali started to retrace his steps. Security camera footage shows three soldiers moving ahead, to within 80 meters of him. Suddenly two shots are heard. The mentally disabled young man collapses, dead

|

| Mohammed Khabali |

Here’s the stick. The bereaved brother removes the black plastic that’s wrapped around it reverently, as if it’s a holy relic. It’s a broomstick, stained with his brother’s blood. It’s the stick he was carrying under his arm as he tried to move away from Israel Defense Forces soldiers approaching him on Jaffa Road in downtown Tul Karm, a street of restaurants and cafés. He was shot from a distance of about 80 meters; the bullet slammed into his head from behind.

How can it be claimed that he endangered anyone from that far away?

Truly understand Israel and the Middle East, from the most trustworthy news source in the region >>

The street was relatively quiet. A small number of young people winding up the night at the coffee houses – and about 30 soldiers opposite them. The security camera at one of the restaurants shows 2:24 A.M. From the video provided by that camera and three others along the street, whose footage was obtained by B’Tselem, the Israeli human rights organization, we see no stone throwing, no large groups milling around. What is seen are three soldiers moving forward, ahead of the rest of their unit. One shot is heard from a distance, and another; two soldiers apparently fired simultaneously. The person seen carrying a stick and walking on the other side of the street, away from the approaching soldiers, falls to the ground, face down. For a second he tries to lift his head – before dying. Another young man is hit in the leg. The soldiers leave in a hurry.

The B'Tselem footage of the incident.

End of operation. End of the short life of Mohammad Khabali, whom everyone here called “Za’atar” affectionately (after the popular seasoning made of wild hyssop). Mentally challenged from birth, he never hurt a soul and helped local café owners clean up at night in return for a free smoke on the narghile; occasionally he would beg for a handout from a passerby. It’s doubtful that the soldier who shot him knew whom he was shooting; it’s even more doubtful that would have cared. He killed Za’atar for no apparent reason and inflicted another disaster on his already unfortunate family, which lives not far away from town in the Tul Karm refugee camp, one of the West Bank’s poorest.

An intimidating pile of garbage greets visitors at the gates of the refugee camp; workers wearing United Nations shirts are loading refuse onto a garbage truck. The Tul Karm camp is the larger of two refugee camps that abut the city on its eastern side. (The other is Nur a-Shams.) Graffiti of a prisoner in an Israel Prisons Service uniform is painted on a wall, a young man in a wheelchair sits in front of one of the houses, the narrow alleys are also littered with garbage.

Neglect is pervasive here. Garbage swirls even around the shattered monument commemorating the 157 inhabitants of the camp who were killed until between 1987 and 2003, during the two intifadas. The monument was erected at the site where at least 10 young people were killed in the second intifada by IDF snipers who positioned themselves on the roof of a high building nearby. A new, more up-to-date monument is planned, we’re told by the camp’s director of services, Faisal Salami. A cluttered store selling scraps, second-hand items and old trinkets is bursting at the seams. It seems like all of Israel’s schmattes have ended up here.

Entering one of the houses, we climb to the second floor: It is the home of the Khabali family and of the camp’s most recent martyr. Exposed electrical cables adorn the walls, on the sink is an old car mirror – the apartment’s only mirror. We will soon be joined by the bereaved father, Khossam Khabali, his legs incapacitated from a childhood disease; he ascends the stairs with great difficulty, leaning on a cane, both legs disfigured. He’s 54 years old and trying in every way possible to provide a living for his nine children, two of whom – the dead son and one of his brothers – have suffered from mental impairment. Khabali works as a guard in the Tul Karm Municipality, hauls fruits and vegetables to the market on a mule-drawn cart, and is an occasional undertaker in the local cemetery. No, he replies, he did not dig his son’s grave.

His face is a study in grief and suffering. Mona, his wife, a heavyset woman of 50, speaks about her dead son in a whisper. The shock is still palpable here.

Last Monday, they relate, Mohammad was at home and in good spirits. He helped his father fix the mule cart. For supper he had makluba, a chicken and rice dish that his mother prepared, and at about 7:30 he left for the cafes on Jaffa Road, as he did every evening. Before leaving, he asked his mother if she needed anything.

|

| Mohammed Khabali's parents (center) at the Tul Karm refugee camp, December 11, 2018.Alex Levac |

He would usually get home around 1 A.M., after straightening and cleaning up the cafes. This time he didn’t return. At about 3 A.M., distraught young men arrived at the house and woke up the eldest son, Ala, who roused his parents: Mohammad had been killed. Khossam asked one of his daughters to check on the camp’s Facebook page whether it was a mistake, and discovered, to his horror, that the victim was indeed his Mohammad. In a daze, he hurried to the Thabet Thabet Hospital in the city, where he saw his son’s body, a hole in the back of his neck. Death had claimed him at age 22.

Mohammad attended school until sixth grade, but didn’t understand a thing, his parents say. Already at the age of 3 they noticed he wasn’t developing like the other children and was mentally disabled. He was their second son. Their next child, Ibrahim, who’s now 18, suffers from the same affliction. Ten days before Mohammad was killed, he and Khossam returned from Amman, where they paid condolences on the death of Khossam’s brother. It was Mohammad’s first – and last – trip out of the country.

According to his Aunt Latifa, who came to Tul Karm for the funeral, he was thrilled to be in Amman. Video clips show him dancing and singing at the home of relatives in the Jordanian capital, a day before returning to the refugee camp. There’s also a selfie that Mohammad took. He helped his uncles harvest and sort olives – that too was captured on video and in other photos.

In the last picture taken of him, Mohammad can be seen holding a small Koran and seemingly reading from it, though he didn’t know how to read or write. That shot was taken in one of the Jaffa Road coffee houses, about an hour and a half before soldiers killed him. Some clips show him speaking, but his speech is slurred, unclear. Allah have mercy, his aunt sighs.

|

| Mohammed Khabali's funeral, Tul Karm refugee camp, December 4, 2018.AFP |

After father and son returned from Amman, discussions began about the wedding of the eldest, Ala. Mohammad told his parents that he’d like to be the next to get married. Mohammad was never stopped by soldiers, never got into a quarrel with anyone, and appears to have been much loved in the camp and in the city, partly because of his impairment. The narghile was his way of relaxing, his escape.

After leaving the family with a heavy heart, we drive to the scene of the killing. Tul Karm’s main street for entertainment begins at Kadoorie Technical University, at the city’s western edge, and ascends to the town center: stores, computer game arcades, restaurants, cafés – one of which is for women only, its windows blacked out. Some of the places are stylishly designed. There’s Café Bianco, Café Al-Shelal and opposite them a wall painting of Mahmoud Darwish, the Palestinian national poet.

On the night between Monday and Tuesday of this past week, some 200 soldiers invaded the city, according to residents’ estimates, and scattered to a number of sites. Routine. A group of about 30 soldiers raided two houses just off Jaffa Road and then proceeded to the main street. They didn’t detain anyone. The coffee houses were already mostly closed, the A-Sabah hummus restaurant was about to open to welcome workers who set out to their jobs in Israel in the middle of the night.

The soldiers gathered next to the Al-Fadilia boys school, the city’s veteran educational institution, at one end of the street. The young people who emerged from the cafés exchanged curses with the soldiers, some threw stones at them from a distance. According to Abd al-Karim Sa’adi, a field investigator for B’Tselem, who carefully collected evidence immediately after the killing as though he were from a police forensic unit, including footage from all the security cameras on the street, the stones landed halfway between the young people and the soldiers. No one was hit.

|

| A memorial for those killed at the Tul Karm refugee camp. Alex Levac |

In Sa’adi’s estimation, no more than 15 or 20 young Palestinians confronted the soldiers, from some distance. One of them told Mohammad, “Za’atar, you should get out of here.” As the video from one camera shows, Za’atar turns around and starts to walk away from the soldiers. Not running but slowly walking. Then he’s shot in the head, from behind.

In a statement to Haaretz this week, the IDF Spokespersons Unit said, “Last week a Military Police investigation was launched. At this stage it can be noted that during operational activity of Israeli soldiers in Tul Karm, a violent riot erupted and dozens of Palestinians hurled rocks towards the fighters. In response, the soldiers used riot-dispersal means and live fire. It was reported that one Palestinian was killed and another injured [in this incident]. When the army finishes its investigation, the conclusions of the probe will be examined by the military prosecutor. The incident is also being probed at the command level.”

B’Tselem has released the following statement: “Video footage from four security cameras installed on three separate buildings along the street shows that the area was perfectly quiet and that there were no clashes there with soldiers… The video footage and the eyewitness accounts collected by B’Tselem from people who were near Khabali show no absolutely no of sign of any ‘disturbance,’ stone-throwing or use of crowd control measures. Quite the contrary: the soldiers are seen walking unhurriedly, the Palestinians are seen talking amongst themselves, and then the soldiers fatally shoot Khabali in the head from a considerable distance. The lethal shooting was not preceded by a warning, was not justified and constitutes a violation of the law.”

A few faded bloodstains are still visible on the asphalt where Khabali’s body was dragged away after the shooting. He died on the spot, his head bleeding profusely, Sa’adi says.

Fine Italian espresso is served in the café opposite, and two colorful photographs are hanging on the wall. One is of a large drone with the Israel Air Force symbol on its tail, the other of an IAF Fouga early fighter plane in the skies above Israel. The proprietor says he erased the squadron numbers before hanging them. He bought the two pictures in Tul Karm’s flea market.

Mohammad Khabali, aka “Za’atar,” is now buried not far from here, in the martyrs section of the cemetery.