Uri Avnery was the last Zionist who genuinely supported equality

|

| Uri Avnery marching with Gush Shalom peace activists, 2002. Photograph: Mike Nelson/AFP/Getty Images |

Uri Avnery, who died on 20th August aged 94 was a remarkable political activist. Avnery fought in Israel’s War of Independence in 1948 (or the Nakba) and he defended that war as a defensive war. Avnery became a life long campaigner for peace as well as a political maverick. He edited the magazine Haolem Hazeh for close on 40 years and when it became the target of Israeli Labour’s state repression he stood for and was elected to serve in the Knesset.

|

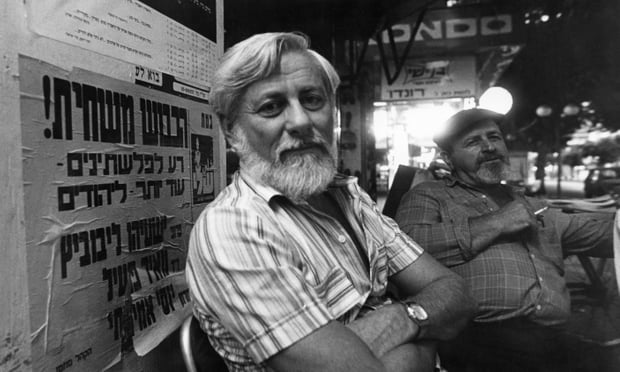

| Uri Avnery in 1980, working as a journalist and publisher of the magazine HaOlam HaZeh. Photograph: Ullstein Bild/Getty Images |

Haolem Hazeh was a left-wing muck racking journal that attracted the ire of the Israeli Labour establishment. It printed the story of how the Iraqi Jewish community, the worlds oldest Jewish community was forced out of the country, not by anti-Semitism but by Zionist agents planting and throwing bombs into Jewish cafes and even synagogues in order to simulate the appearance of anti-Semitism. It took the side of Israel’s Oriental/ Misrahi Jews against the Ashkenazi Labour Establishment which saw the Iraqi and other Middle Eastern Jewish communities as providing the Jewish working class of Israel, once they had been de Arabised.

It is arguable whether or not Avnery was a Zionist since he believed in a Jewish or Hebrew State alongside a Palestinian state but one inclusive of its Arab inhabitants. He was part of the Canaanite group who believed in cutting Israel off from the Jewish diaspora and becoming an Israeli nation.

What Uri didn’t or refused to understand was that Zionism was a settler colonial state and that Zionism could not simply be abandoned once the Israeli state had been created. The character of the Jewish state was indelibly fixed by the manner of its birth. It was condemned to be a bastard state. Zionism inevitably meant the displacement of the Palestinians from their land prior because of the need to secure a Jewish majority in a land where Palestinians were the majority, even in the part allocated by the UN to a Jewish state. This ensured that process of colonisation and discrimination would continue after 1948. A Jewish state also meant that Arabs would be consigned to the margins, an after thought.

|

| Avnery, pictured in 2011, ‘was badly beaten and stabbed by Israeli fascists’ (Getty) |

Yet despite this Uri Avnery was one of the very few Zionist supporters who genuinely believed in the 2 State Solution. Most of those who profess support for 2 states do so because, like the Israeli Labour Party, they want segregation between Jew and Arab whilst seeking to ensure that Israel is not officially an apartheid state, as it is now, ruling over millions of people who haven’t even the most minimal democratic or civil rights. Avneri sincerely condemned the occupation and the harsh military regime which ruled over the Palestinians whereas the hypocrites of the Jewish Labour Movement and Labour Friends of Israel, who say they support two states in fact support the military occupation, the checkpoints, arbitrary imprisonment, torture and all the other practices that go along with military rule.

I had my disagreements with Uri in particular his opposition to BDS in for example Uri Avnery – The Muddle Headed Zionist Opposes Boycott. InVeteran Israeli Peacenick Clings to Zionist Delusions I posted an article by Jonathan Cook which criticised Avnery’s argument that the position of Israel’s Arab population was akin to the discrimination against national minorities in Europe. I also reprinted in Uri Avnery - Supporter of 'Peace' and the Palestinian Police Statelet an article by Israeli anti-Zionist Tikva Honig Parnass Support of the Israeli Peace Camp for the Autocratic Palestinian Regimewhich detailed one of the problems of Avnery’s two state position. It meant support for the Palestinian Authority, which is a nasty little police statelet, the subcontractor for Israel’s military occupation.

However when Israel killed 9 people on the Marva Marmara, a ship trying to break the blockade of Gaza, I had no hesitation in reprinting Uri’s excellent articleWho is Afraid of a real Inquiry?.

Uri Avnery was a maverick, but a sincere maverick and also a brilliant journalist with a flare for writing. I can remember discussing with Moshe Machover whether or not it would be fair to classify Uri as a Zionist or not. I don’t think we ever decided. One thing is for certain. Uri was one of the very few Zionists, if that is what he was, who genuinely and sincerely believed in equality between Jew and Palestinian and who was sincere in his desire for a fully independent Palestinian state and an end to the Occupation.

That was why Uri supported indeed initiated a Boycott of Settlement Produce but not of Israeli goods.

Uri wrote regularly for some 25 years a regular Friday article. Appropriately enough his last article entitled Who the Hell Are We?, written in the aftermath of the passage of Netanyahu’s Jewish Nation State Law, posed the question that has dogged the Israeli state - what is the identity and nationality of those who inhabit that State.

Uri’s conclusion was that there is a Hebrew not a Jewish people in Israel which encompasses the Arab inhabitants of the State. In other words Uri was rejecting the idea that Israel should be a state of only its Jewish inhabitants and the even more absurd idea that the Jews of Israel are part of a wider Jewish nation, encompassing Jews throughout the world.

Uri Avnery, the Israeli optimist who played chess with Yasser Arafat, has died – he was one of my few Middle East heroes

Uri Avnery, the Israeli optimist who played chess with Yasser Arafat, has died – he was one of my few Middle East heroes

Robert Fisk's appreciation recalls the time he, Fisk, had walked across the bodies of up to 2,000 Palestinians, mainly women and young children, who had been slaughtered in Beirut by Israel’s fascist Phalangist allies under the watchful eyes of Israeli troops. Not only had Israel’s military kindly lit up the sky with flares in order that the Phalange could see who they were killing but survivors who fled to the perimeter of the camp were turned back into the hell of the camps. Fisk asked Avnery how the survivors of the Holocaust and their children could commit such an atrocity:

“I will tell you something about the Holocaust. It would be nice to believe that people who have undergone suffering have been purified by suffering. But it’s the opposite, it makes them worse. It corrupts. There is something in suffering that creates a kind of egoism. Herzog [the Israeli president at the time] was speaking at the site of the concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen but he spoke only about the Jews. How could he not mention that others – many others – had suffered there? Sick people, when they are in pain, cannot speak about anyone but themselves. And when such monstrous things have happened to your people, you feel nothing can be compared to it. You get a moral ‘power of attorney’, a permit to do anything you want – because nothing can compare to what has happened to us. This is a moral immunity which is very clearly felt in Israel. Everyone is convinced that the IDF is more humane than any other army. ‘Purity of arms’ was the slogan of the Haganah army in ’48. But it never was true at all.”

I shall certainly miss his regular Friday article which can be found here! Below are two appreciations of Uri and I also recommend Jonathan Steele’s excellent obituary.

As Diana Buttu, a former advisor to the Palestinian negotiating team observed‘His (Uri’s) death, in a lot of ways, marks the end of the two-state solution – he was the last activist I know of that was really calling for it.”

Tony Greenstein

Adam Keller, who spent 50 years working alongside Uri Avnery, remembers the man who hoped for a warm embrace between an Israeli and a Palestinian president.

By Adam Keller

|

| Uri Avnery (Yossi Gurvitz) |

How to sum up in a few words 50 years of political partnership, which was also an intimate friendship, with the person who, I believe, had the most influence on me?

The starting point: summer of 1969. A 14-year-old from Tel Aviv, during the summer between elementary school and high school, I notice an ad in HaOlam HaZeh newspaper asking for volunteers at the election headquarters of the “HaOlam Hazeh – Koah Hadash” (“New Power”) party. I went. In a small basement office on Glickson Street, I found three teenagers folding propaganda flyers into envelopes. To this day, the smell of fresh print takes me back to this very moment. Two hours later, we heard a commotion outside. Member of Knesset Uri Avnery, the man whose articles brought us to this office in the first place, walked in. He was returning from an election campaign in Rishon LeZion. He exchanged a few words with the volunteers, thanked us for our help, and went into a meeting room with his aides.

At that point, it was not Uri Avnery’s opinions on the Palestinian issue that motivated me to volunteer for the campaign. My own opinions on the matter were not fully formed yet. Only two years prior, in June of 1967, I had shared with many others in celebrating the fact that Israel expanded into “new territories.” I would not have even imagined that I would eventually dedicate most of my life to trying to get Israel out of those territories. I was attracted to Uri Avnery’s party primarily because it was a young, fresh political party that challenged the old, rotten establishment parties, and because it was opposed to religious coercion, and advocated for separation of religion and state, public transportation on Shabbat, and civil marriage.

A few weeks after I began volunteering, I left a note on Uri’s desk with a few questions: can we really make peace with the Arabs? Should we give back all the territories Israel occupied, or only some? And what will happen with the settlers? (The settler population at the time was a tiny fraction of what it is today.) A week later, I received a letter in the mail – three pages of detailed answers to each one of my 10 questions. I still have that letter. I have no doubt that Uri wrote it himself – his writing style seeps out of every word. He took the time and energy, in the middle of running a political campaign, to provide thorough answers to the questions of a 14-year-old teenager. I think it turned out to be a profitable investment.

The end point: Friday, August 3, 2018. A years-long political partner of Uri Avnery, at 63 years old, I receive his weekly column, as I do every Friday. In this article, he wrote about the Jewish Nation-State Law and Israel’s national identity, and whether it was Jewish or Israeli (he, of course, strongly advocated for an Israeli identity). As I had done many times before, I wrote him an email commenting on the substance of the article, raising some fundamental objections. He suggested we discuss them further next time we meet. I asked for his opinion on the protest against the Nation-State Law, scheduled for the following day by the Druze community. He said he was convinced that the demonstration would not focus on the Druze’s exclusive standing in Israeli society, or the unique bundle of rights they get for serving in the military, but that it will tackle the fundamental principle of equality for all citizens.

|

| Tens of thousands of protesters joined the Druze community in rejecting the Jewish Nation-State Law at Rabin Square in Tel Aviv on August 5, 2018. (Oren Ziv/Activestills.org) |

The last which I will ever hear from him was a one-line message on my computer screen: “I am going to the Druze protest tomorrow.” I assume that he did read what I had written him, and that he woke up the next day with the intention of participating in the protest. In the evening, when I was standing amidst the large crowd that amassed in Rabin Square, I assumed he was standing somewhere around. I rang his phone twice but there was no reply, chalking it up to bad reception (which is common during mass rallies when very many people use their mobile phones all at once). In retrospect I know that by then he had already been admitted to an emergency room at Ichilov Hospital, never to regain his consciousness. It was the activists who planned to give him a ride to the demonstration who had found him lying on the floor of his apartment.

What filled the 50 years between the start and end points? The HaOlam Hazeh – Koah Hadash party, which merged into Peace and Equality for Israel, a political party known as Shelli in Hebrew; the Council for Israeli-Palestinian Peace, which managed meetings with the Palestinian Liberation Organization and became a faction of Shelli; the Progressive List for Peace, which we joined after Shelli disintegrated; and then Gush Shalom. So many meetings, marches, protests and conversations. So many memories.

Standing side by side, holding posters at a protest to prevent the closure of Raymonda Tawil’s news agency in East Jerusalem. The photo that Avnery’s wife, Rachel, took of that demonstration is still up on the wall of the room I am writing these very words in. A conversation with Avnery the day that HaOlam Hazeh, which he edited for 40 years, officially shut down. “I know this is a difficult day for you,” I said. He answered: “The paper was a tool, serving a purpose. We shall find other tools.”

|

| PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat being interviewed by Uri Avnery in west Beirut. (Photo by Anat Saragusti, courtesy of Uri Avnery) |

It is early 1983. Uri Avnery, Matti Peled and Yaakov Arnon, known us the “Three Muskateers,” come back from a meeting with Yasser Arafat in Tunisia. As soon as he lands at the airport, he hands me photos of the meeting, and I bounce from one newsroom to another across Tel Aviv to distribute them in person. I then take a shared taxi to Jerusalem where Ziad Abu Zayyad, editor of the Palestinian Al-Fajr (“The Dawn”) newspaper, waited for me.

A bit later in 1983, the radio announcing the assassination of Issam Sartawi, a PLO member who often met with Avnery and was a close friend to him, and my phone call to Uri informing him of the sad news. The frustrating, endless phone calls in the couple of days that followed proved to us that it was impossible to rent a hall in Tel Aviv to commemorate a PLO man – even one who advocated for peace with Israel and was killed for it.

December 1992. Prime Minister Rabin, who had not yet signed the Oslo Accords and had not yet become a hero of peace, expels more than four hundred Palestinian activists to Lebanon, and we put up a protest tent in front of the Prime Minister’s Office. It is a cold Jerusalem winter, and it is snowing, but inside the tent that was donated by Bedouins from the Negev, it feels warm and cozy. Uri, Rachel, myself and my wife Beate join other activists in a long conversation with Sheikh Raed Salah, head of the northern branch of the Northern Branch of the Islamic Movement in Israel, on Judaism and Islam, and how religion and politics converge and clash.

In 1997, in the middle of a protest in front of Har Homa – Netanyahu’s flagship settlement – Uri’s stomach wound, which he had been carrying since the war in 1948, breaks open. A Palestinian ambulance clears him to Al-Makassed Hospital in East Jerusalem; we are all anxious. Rachel tells me, “even though I do not believe in God, I am praying.” But Uri recovers and lives on for 21 more years of intensive political activity.

May 2003, the Muqata’a (presidential compound) in Ramallah. That afternoon, there was a suicide bombing in Rishon LeZion, and Prime Minister Ariel Sharon drops a hint that he might send an elite IDF unit to “handle” Yasser Arafat that night. We are among 15 Israeli activists who go to Ramallah to serve as human shields. We call the media and tell them that “for the Prime Minister’s information, there are Israeli citizens sitting outside of Arafat’s door!”

|

| Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, U.S. president Bill Clinton, and PLO chairman Yasser Arafat at the signing of the Oslo Accord (photo: Vince Musi / The White House) |

Arafat shows Uri his gun and says, “if they come, I have a bullet in here for myself.” We spend an entire night at Arafat’s door, having conversations with young Palestinian guards in a mix of Arabic, Hebrew, and English, paying attention to every sound. Then, it is dawn, and we understand that we made it through the night safely, and that the soldiers will not be coming.

Another long, relaxed conversation when we stopped to eat something on our way back from a Progressive List meeting in Nazareth: “The Crusaders were here before us, they came from Europe and established here a country that lasted 200 years. Not all of them were religious fanatics. Among them were people who spoke Arabic and had Muslim friends. But they were never able to achieve peace with their neighbors or adapt to this region. They had temporary agreements and ceasefires, but were not able to gain real peace. Acre was their ‘Tel Aviv,’ and when it fell, the last Crusaders were thrown into the sea – literally. Those who do not learn from history are bound to repeat it.”

“If I ever get the chance to serve as a minister, I would want to be education minister. That is the most important portfolio in the cabinet. The defense minister may be able to send soldiers to die in war, but the education minister can shape children’s consciousness. The policies of today’s education minister will still bear manifest results in 50 years, when today’s children become grandparents and talk to their own grandchildren. If I were the minister, the first thing I would do is remove the [biblical] Book of Joshua from the curriculum. That book advocates genocide, plain and simple. It is also a historical fiction – the events it describes never happened. Rachel was a teacher for 40 years, and every year she succeeded in avoiding teaching this trash.”

Rachel accompanied him everywhere, an active partner to everything he did, editing his articles and dealing with the all the logistics of organizing protests. We all knew she was a hepatitis B carrier, a time bomb that might explode at any minute. And when it finally did, Uri spent six months with her in the hospital, day and night. He almost had disappeared from political life. One day, I happened to bump into him in the hallway of Ichilov Hospital as he was pushing her in a wheelchair, from one checkup to another.

In her final weeks, someone told Uri of an experimental treatment that could save Rachel’s life. Although he knew the chances were slim, Uri spent large sums of money to purchase the medication in America and have it flown to Ben Gurion Airport, and from there, transported directly to the hospital. When she passed away, Uri asked that nobody contact him for three days, and he completely disengaged from the world. Once those three days were over, he went back to his routine of protests and political commentary – or so it seemed.

How to finish off this article? I will go back to 1969, to an article by Uri which I read under the table during a very boring class in eighth grade. I still remember it, almost word for word; it was a futuristic article that attempted to imagine what the country would look like in 1990. The page was split into two parallel columns, representing two parallel futures. In one of the futures, Independence Day in 1990 is marked by a tremendous manifestation of military power, with new tanks on display in Jerusalem. Prime Minister Moshe Dayan congratulates IDF soldiers who are on alert in the Lebanon Valley and the Land of Goshen near the Nile, and declares: “We shall never give up the city of Be’erot (formerly Beirut), this is our ancestral homeland!”

In the second future, on Independence Day in 1990, festive receptions are being held at Israeli embassies across the Arab world, but the most moving photo was captured in Jerusalem, of a warm embrace between Israeli President Moshe Dayan and Palestinian President Yasser Arafat.

Adam Keller is an Israeli peace activist who was among the founders of Gush Shalom. This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.

Veteran left-wing journalist and peace activist Uri Avnery dies at 94

By +972 Magazine Staff

Uri Avnery (left) marches alongside his wife Rachel during a rally against the occupation of the West Bank and the siege on Gaza. (Oren Ziv/Activestills.org)

Uri Avnery, one of Israel’s most prominent journalists and a seminal peace activist who was among the first Israelis to advocate for a sovereign Palestinian state, died in Tel Aviv on Monday morning. He was 94 years old.

Born Helmut Ostermann to a bourgeois family in Beckum, Germany in 1923, Avnery’s family moved to Palestine in 1933, shortly after the Nazis came to power. They settled in Tel Aviv. Just a few years after their arrival, Avnery joined the Irgun, the pre-state right-wing Zionist militia. Too young to take part in its militant actions, which included attacks against British soldiers and Arab civilians, Avnery distributed leaflets and edited the Revisionist journal Ba-Ma’avak (“In the Struggle”).

He left the Irgun in 1942, because he was uncomfortable with its harsh anti-Arab position, and joined the Givati Brigade of the Haganah during the 1948 War. During the war he wrote dispatches from the field for Haaretz newspaper, which he later compiled into a book. Avnery was wounded twice — the second time, toward the end of the war, seriously; he spent the last months of his army service convalescing and was discharged in the summer of 1949.

Avnery initially supported the idea of one state, in which a single nation would arise as a union of Arabs and Hebrews — the latter a term he preferred over Jews, since he advocated a state for the Hebrew nation rather than the Jewish people.

During the mid-1960s, Avnery believed that the national Hebrew movement was a natural ally of the Arab nation; he advocated cooperation between the two, under a joint name. By the end of the June 1967 war, however, Avnery changed his views: He advocated the establishment of a Hebrew state alongside an Arab one, as per the 1947 UN Partition Plan.

In 1950 Avnery, together with journalist Shalom Cohen, bought the failing HaOlam HaZeh (“This World”) newspaper in 1950. As editor-in-chief, Avnery turned the paper into a dissident and anti-establishment tabloid that mixed exposés on the corruption of the ruling Mapai government (Ben Gurion’s party, which dominated Israeli politics from 1948 until 1977) with gossip pieces and photographs of nude women.

Commonly derided by Israeli leaders, including Prime Minister Ben Gurion, the paper’s editorial position was anti-militarist. It published investigative reports that exposed the government’s racist and discriminatory policies against Mizrahi Jews and other ethnic minorities, opposed the military rule that was imposed on Israel’s Arab citizens from 1948-1966, and was the first to publicize the Yemenite Children Affair.

During the years he was editor of HaOlam HaZeh, Avnery was victim of numerous physical attacks. One ended with both his arms broken. In 1975, he was seriously wounded after an assailant stabbed him on his own doorstep.

|

| Uri Avnery, left, with the Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat during a meeting in the West Bank city of Ramallah, 2002. Photograph: Brennan Linsley/AP |

The Shin Bet, Israel’s General Security Service, saw in HaOlam HaZeh a serious threat to the state and listed Avnery as the top enemy of the government. The newspaper’s office was bombed several times, with a 1972 arson attack destroying its entire archives. At one point, the Shin Bet even published its own tabloid, Rimon, in order to discredit HaOlam HaZeh and put it out of business. Rimon would operate for only three years before shutting down.

Avnery decided to enter politics in 1965, after the Knesset passed an anti-defamation law that sought to clamp down on HaOlam HaZeh. He founded the left-wing movement Koah Hadash (New Power). After his election to the Knesset in 1969, Avnery dedicated his parliamentary activities to promoting peace with Israel’s neighbors, fighting against religious coercion by the ultra-Orthodox, and championing civil liberties. He would return to the Knesset in 1979 with the dovish Sheli party, and in 1981 was the first MK to hold up the Palestinian flag alongside the Israeli one in the Knesset plenum.

In 1982, at the height of the Israeli army’s siege on Beirut, Avnery and a group of Israeli journalists, including Anat Saragusti, met with PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat in the city — one of the first times Israelis met with the Palestinian leader (Charlie Bitton and Tawfik Toubi, both members of Knesset from Israel’s communist party, met with Arafat and the PLO leadership two years prior). The meeting came almost a decade after Avnery made contact with one of Arafat’s envoys. Upon his return from Lebanon, members of the Israeli government called for Avnery to be tried for high treason. Avnery would continue to meet with Arafat in subsequent years, including in 1994, after the Palestinian leader arrived in the occupied territories under the Oslo Accords.

|

| Uri Avnery (center) sits between Arab MK Ahmad Tibi (L), and Likud MK Zeev Elkin (R) in the Supreme Court in Jerusalem, February 16, 2014. (Flash90) |

Avnery would eventually split off from Sheli with a group of Arab and left-wing movements to form the Progressive List for Peace, which called for equality for Israel’s Palestinian citizens and an end to the occupation. In 1993, feeling that Israeli peace groups did not take a strong enough stance against the government’s repressive measures — which included the 1992 expulsionof 415 Hamas members from the occupied territories — Avnery formed the peace group Gush Shalom. He remained the head of the movement, helping organize demonstrations against the occupation and the siege on Gaza and publishing a weekly column until his death.

From the beginning of his journalism career, mainstream Israeli opinion held that Avnery’s writing was subversive and anti-Israel. In his later years he was the subject of controversy after he published articles attacking Russian immigrants and Mizrahi Jews, accusing them of responsibility for Israel’s rightward shift.

Uri Avnery’s wife Rachel died in 2011. They were married for 58 years and chose not to have children, so that they could dedicate their lives to political struggle.