Remembering the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

Last week was the 75th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. You would have been forgiven for having missed it. The anniversary of the founding of the Israeli state, which was also on 19th April this year, took precedence in the mass media and the Zionist press. Given the choice between a tale of Jewish heroism against impossible odds, fighting fascism and racism or tales of heroic Israelis massacring Palestinian civilians and creating ¾ million Palestinian refugees, there was no choice.

Earlier in the year we had Holocaust Memorial Day, a saccharine event whose primary purpose is to depoliticise the Holocaust, the how and why it happened. No uncomfortable comparisons between New Labour and Theresa May’s ‘climate of extreme hostility’ to immigrants and the failure to rescue Europe’s Jews. No searing questions about how much of the Establishment and their rabid press supported Hitler up and until the invasion of Poland. Even fewer questions about the role of the Zionist movement during the Holocaust.

|

| Poland stands at attention for those slain (Photo: Reuters) |

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was however commemorated in Poland. There were the government's own commemorations led by the President Andrzej Duda but hundreds attended independent commemorations, refusing to attend those organised by a government which, earlier in the year, passed legislation making it a criminal offence to accuse Poles of having collaborated with the Nazi occupation (which many did).

|

| German soldiers direct artillery against a pocket of resistance during the Warsaw ghetto uprising. Warsaw, Poland, April 19-May 16, 1943. — US Holocaust Memorial Museum |

It is not hard to see why the Zionist movement and their court servants – the John Manns, Joan Ryans, Ruth Smeeths and Luciana Bergers, should have little to say about the Uprising. For a start it was led by an anti-Zionist Jewish socialist party the Bund, [the wrong sort of Jews!] who had the loyalty of the overwhelming majority of Polish Jews. Secondly fighting anti-Semitism has always been deprecated in Zionist circles (unless it is the type of ‘anti-Semitism’ that is anti-Zionism). Zionism was established on the basis of not fighting anti-Semitism because anti-Semitism was inherent in the non-Jew, it was futile. Antisemitism was deemed by the Zionist movement to be the product of Jewish ‘homelessness’. In the words of the founder of Political Zionism, Theodor Herzl, who wrote this at the time of the Dreyfuss Affair:

|

| Theodor Herzl - founder of Political Zionism - tolerant of anti-semitism |

Theodor Herzl

‘In Paris... I achieved a freer attitude towards anti-Semitism, which I now began to understand historically and to pardon. Above all, I recognise the emptiness and futility of trying to 'combat' anti-Semitism.' [Diaries, p.6]

|

| Poles laying flowers on the monument to the fallen heroes |

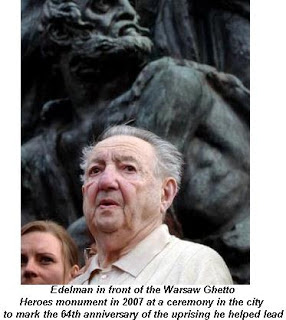

The Warsaw Ghetto was ignored and forgotten by the Zionist leaders in Palestine. Zionist leader Yitzhak (Antek) Zuckerman asked why no-one left Geneva, Istanbul or Sweden, ‘if only to serve as a ‘gesture, a sign, a hand extended as a token of sharing our fate’?’ Only the Bund and the AK sent emissaries into the ghetto. Other movements in Europe sent their emissaries from one ghetto to the next [Dinah Porat, p. 228, The Blue and Yellow Stars of David]. To the Zionist movement in Palestine, the fate of the Warsaw Ghetto was irrelevant. Their sole objective was achieving a Jewish state. The young Zionists who fought first had to rebel against their own Zionist parties. Zionism was irrelevant. Marek Edelman, the last Commander of the Uprising and a member of the Bund describes how:

‘We joined hands with all Jewish Zionist underground organizations. Our comrades lived and worked with the others just as members of a close family. A mutual aim united us. During this entire period of over half a year, there were no quarrels or struggles, which are common among adherents of different ideologies. All overworked themselves in organising the mutual defence of our dignity.’[Edelman, The Ghetto Fights, pp. 110-111. Citing Second report of the Jewish workers underground movement, 15.11.43].

Marek Edelman described how ‘the cornered partisans defended themselves bitterly and succeeded, by truly superhuman efforts, in repulsing the attacks’ as well as capturing two German machine guns and burning a tank. [Edelman, p.76].

The role of the Bund and Edelman in the Warsaw Ghetto Revolt has been airbrushed out of history by Zionist holocaust historians. The Revolt has become another Zionist foundational myth. [The last Bundist, Moshe Arens,] Today Zionism uses the Revolt for propaganda purposes, suggesting that the Resistance was solely composed of young Zionist fighters.

There was another reason for Zionist hostility to Edelman. Edelman had written an open letter to the Palestinians asking them to stop the bloodshed and enter into peace negotiations. The letter caused outrage in Israel because Edelman did not mention the word “terrorism.” Israeli leaders were particularly incensed by its title: ‘Letter to Palestinian partisans’.

Ha'aretz, 9.8.02.

|

| Smoke from the Treblinka uprising, as seen from a railroad worker. (Credit: UtCon Collection/Alamy) |

‘Mr Edelman … wrote in a spirit of solidarity from a fellow resistance fighter, as a former leader of a Jewish uprising not dissimilar in desperation to the Palestinian uprising in the occupied territories. He addressed his letter to “commanders of the Palestinian military, paramilitary and partisan operations – to all the soldiers of the Palestinian fighting organisations. This set up a howl of rage in the Zionist press, who reminded their readers that Mr Edelman, despite his heroism in the 1940s, is a former supporter of the anti-Zionist socialist Bund, and can therefore not be trusted.’ [Palestine's partisans, Paul Foot, Guardian, Wednesday August 21, 2002,]

What was particularly irksome was that Edelman had consciously compared the structures of the resistance movement in Warsaw to that of the Palestinians.’ [The Last Bundist].

When Edelman died, the President of Poland attended his funeral in Warsaw on 9th October 2009 and there was a fifteen-gun salute. Because of his support for the Palestinians, not even the lowliest clerk in the Israeli Embassy attended. [Zionism Boycotts the Funeral of Marek Edelman, 15.10.09.] Moshe Arens, the former Likud Foreign Minister, interviewed Edelman as part of his research into the history of the Revisionist National Military Army ZZW, which fought separately in Warsaw: ‘I knew his views on Israeli politics, and did not discuss the situation in the Middle East, but as we parted I said “You must make peace with the Arabs.” Edelman received Poland's highest honor, and the French Legion of Honor medal but ‘he died not having received the recognition from Israel that he so richly deserved.’

see also

see also

Hero of Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Marek Edelman, Dies at 86, Ha'aretz 4.10.09.,

‘Marek Edelman - Death of an anti-fascist hero of the Warsaw Jewish Resistance’

‘Marek Edelman - Death of an anti-fascist hero of the Warsaw Jewish Resistance’

The Revisionist Zionists made up the leadership and ranks of the Jewish police and the leadership of ZOB had contempt for them. The ZZW obtained their arms via their Polish fascist friends. Stiff resistance to the Nazi invasion of the Ghetto came from the Revisionists, who were based at 7-9 Muranowska Square and the corner of Muranowska and Nalewki streets. For two days the Polish and Jewish Star of David flags flew, visible to thousands of Poles on the Aryan side. [S Beit Zvi, p.353, Post-Ugandan Zionism on Trial, A Study of the Factors That Caused the Mistakes Made by the Zionist Movement During the Holocaust, 1991, Zahala, Tel Aviv]

Some five to six thousand Jews are estimated to have escaped from the ghetto to the ‘Aryan’ side of Warsaw and to have remained hidden till the end of 1943. In Palestine there was panic that the revolts ‘would ultimately deprive the Yishuv of the cream of Europe’s potential pioneering force.’ Melech Neustadt wanted the youth movements in Palestine to instruct their comrades ‘to abandon their communities, save themselves, and thereby stop the armed uprisings.’ The Zionist youth in Europe, such as Antek Zuckerman and Zivia Lubetkin refused on principle to leave. Hayka Klinger, who arrived in Palestine in March 1944, told the Histadrut Executive that ‘we received an order not to organize any more defence.’ [i] The Zionist leadership sought to extricate the leaders of the ghetto fighters as they were more valuable in Palestine than in leading the resistance in the ghettos. Klinger told Histadrut that ‘Without a people, a people’s avant-garde is of no value. If rescue it is, then the entire people must be rescued. If it is to be annihilation, then the avante-garde too shall be annihilated.’ [Zertal, The Politics of Nationhood, p.33

The Zionist leaders saw the subsequent risings in other ghettos as ‘a kind of betrayal of the overriding principle of the homeland.’ [Zertal, p.44] Yet despite this Ben Gurion later claimed that the heroism of the ghetto fighters owed its inspiration to the Zionist fight in Palestine. The ghetto fighters were ‘retrospectively conscripted’ into the Zionist terror groups. ‘We fought here and they fought there’ according to Palmach commander Yitzhak Sadeh.[Zertal, pp. 25-26]. The resistance of the Jewish ghetto fighters became intertwined with the heroic myth of the Zionist fight for Palestine. See The anti-Zionist Bund led the Jewish Resistance in Poland whilst the Zionist Movement abandoned the Jews

The article below contains a number of mistakes and is slanted towards a Zionist version of events. Nonetheless it is an interesting description of the events of 75 years ago. I also recommend you read Marek Edelman's account of the Ghetto Uprising, The Ghetto Fights.

Tony Greenstein

On this day in 1943, a band of Jewish resistance fighters launched an armed insurrection against the Nazis. They were proud socialists and internationalists.

|

| Jewish resistance fighters during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. WWII War Crimes Records |

On the eve of Passover 1943 — the nineteenth of April — a group of several hundred poorly armed young Jews began the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, one of the first insurrections against Nazism.

For a small group of fighters, realizing — in the lyrical words of one militant — that “dying with arms is more beautiful than without,” an isolated group of Jewish militants resisted for twenty-nine days against a much larger foe, motivated by a desire to kill as many fascists as they could before they themselves were killed. The uprising, etched into the collective memory of postwar Jewry, remains emotive and emboldening.

That their heroism was a crucial part of the war is disputed by nobody today. But less known is the extent to which the uprising, far from being a spontaneous one of the masses, was the product of planning and preparation from a relatively small — incredibly young — group of Jewish radicals.

The Ghetto

Within a few weeks of the Nazi consolidation of Poland, Governor Hans Frank ordered four hundred thousand Warsaw Jews to enter a ghetto. By November 1940, around five hundred thousand Jews from across Poland had been sealed behind its walls, severed from the outside world and plunged into social isolation. Surrounded by a ten-foot-high barrier, the creation of the ghetto meant the relocation of approximately 30 percent of Warsaw’s population into 2.6 percent of the city, the designated area being no more than two and a half miles long and having previously housed fewer than 160,000 people.

In the ghetto, Jews were forced to live in chronic hunger and poverty. Many families inhabited single rooms, and the dire lack of food meant that roughly one hundred thousand people survived on no more than a single bowl of soup per day. The sanitation system collapsed, and disease became rampant. By March 1942 onwards, five thousand people died each month from disease and malnutrition.

The situation was dire — and yet, the initial response of the Jewish community leadership was one of inaction. Following the creation of the Judenrat (Jewish Council) — a collaborationist organization established with Nazi approval to allow easier implementation of anti-Jewish policies — some inhabitants fell into a false sense of security. An attitude permeated the ghetto, proffered through the lens of Jewish history, that Nazism was just another form of persecution that the Jewish people must suffer and outlast.

Others — such as the Hashomer Hatzair militant Shmuel Braslaw — began to recognize a jealous respect for the Germans among the ghetto’s residents. “Our young people learn to doff their caps when encountering Germans,” wrote Braslaw in an internal document, “smiling smiles of servitude and obedience . . . but deep in their hearts burns a dream: to be like [the Germans] — handsome, strong and self-confident. To be able to kick, beat and insult, unpunished. To despise others, as the Germans despise Jews today.”

Against this demoralization, circles of defiance could be found in the self-organization of the left-wing of the Jewish community. Communists, Socialist-Zionists of varying descriptions, and social democrats organized themselves into sections in the ghetto, aiming to transform the misery into meaningful political organization. All parties — the Bund, a social-democratic mass organization that had enjoyed huge pre-war popularity; the Marxist-Zionist youth group Hashomer Hatzair; the left-wing Zionist party Left Poale Zion; and the Communist Party dedicated themselves to this strategy, organizing cells that sought to revive collectivist attitudes among an emotionally crippled and disaffected Jewish youth.

In dark times, the cell structures of youth organizations provided a social and psychological anchor against hunger and depression. “The day I was able to re-establish contact with my group,” wrote the Young Communist militant

Dora Goldkorn, “was one of the happiest days in my hard, tragic ghetto life.” In the project to develop a resistance leadership among the youth, keeping spirits high was crucial; acts of friendship such as the sharing of food were as important as distributing anti-Nazi literature.

By 1942, the various youth organizations felt confident enough to consider the formation of an “Anti-Fascist Bloc.” On the insistence of the Communists, a manifesto was drafted that sought to unite the Jewish left in the Warsaw Ghetto, with the hope of generalizing this political unity across other ghettos.

Calling for a “national front” against the occupation, for the unity of all progressive forces on the basis of common demands and for armed antifascism, the manifesto echoed the pre-war Popular Fronts in its organizational methodology.

The Left Poale Zion enthusiastically joined, as did the Hashomer Hatzair — who re-emphasized their fidelity to the Soviet Union, despite the Kremlin’s opposition to Zionism. The Bund, however, were less reliable, due to their historic anticommunism and rejection of specifically Jewish armed action; a party that resolutely stated Poland was the home for Polish Jews, many Bundists refused avenues other than Polish-Jewish unity of action.

The paper of the Anti-Fascist Bloc, Der Ruf, reached publication twice. Its contents overwhelmingly focused on applauding Soviet resistance and urging the ghetto inhabitants to hold out for imminent liberation at the hands of the Red Army.

The bloc’s fighting squads contained militants belonging to all varieties of labor movement groups, but the lynchpin of the organization was Pinkus Kartin. A stalwart of communism in prewar Poland and a veteran of the International Brigades to Spain, Kartin was a leader both politically and militarily. To the historian Israel Gutman, who himself was active with Hashomer Hatzair in his youth, Kartin “undoubtedly impressed” the underground’s young and inexperienced cadre.

It was the arrest and murder of Kartin in June 1943 that signaled the end for the Anti-Fascist Bloc. His arrest triggered an intense repression against the prominent Young Communists, who saw their numbers decimated and were driven into hiding. It is for this reason that when the Jewish Fighting Organization (ZOB) was founded several months later, the Communists were absent at first — although their political line was upheld and applied by those such as Abraham Fiszelson, a Left Poale Zion leader who had been Kartin’s right-hand man and had befriended him in Spain.

During this period, figures from the right-wing of the Jewish community formed a rival group, the Jewish Military Union (ZZW). Led by the right-wing Zionist group Betar and funded by high society, the ZZW relied upon ex-army officers who could fight orthodox warfare with the Nazis using regular army discipline — unlike the ZOB, which considered itself the armed expression of the Jewish workers’ movement. Furthermore, the ZZW’s connections to Polish nationalists, the antisemitic Polish government-in-exile and the right-wing Revisionist-Zionist movement provoked suspicion among the ZOB leadership.

By contrast, in the eyes of Israel Gutman, the typical ZOB volunteers were “young men in their twenties, Zionists, Communists, socialists — idealists with no battle experience, no military training.” While the propaganda of the ZZW was staunchly nationalistic, the ZOB’s propaganda and literature encouraged antiracist internationalism, offered intellectual positions on the world situation, and debated the labor movement.

Despite the darkness of their times, members of the ZOB belonged to a political tradition that desired a better world, and sought to create it through their struggle.

The Resistance

The ZOB set as its aim an anti-Nazi insurrection. However, it recognized that paramount to achieving this was the strengthening of the organization’s position in the wider community — it was decided that it had to involve the intimidation and execution of Jewish collaborators with the occupiers.

For ZOB militants, collaborators represented an auxiliary wing of fascism that was instrumental in facilitating the deportation of Polish Jewry. To demonstrate that this stance would not be accepted in the ghetto, ZOB militants chose to execute Jewish policeman Jacob Lejkin. For his “dedication” in deporting Jews to Auschwitz, Lejkin was shot, and his example triggered widespread panic in the collaborating establishment. This was followed by the execution of Alfred Nossig in February 1943. Józef Szeryński, the former head of the ghetto police, committed suicide to avoid his own fate.

These acts ensured ZOB’s centrality in the resistance movement, and also encouraged resistance from beyond their ranks. They aimed to prove that challenging collaboration was both possible and a moral duty — and within a short period of time had won many ghetto inhabitants to this position.

As the months progressed, the specter of death became ever-present. Between June and September 1942, three hundred thousand Jews had been deported or murdered, a destruction of the Polish Jewish community. In these desperate circumstances, people lost everyone and many young people began to dispense with anxieties about protecting their families and commit instead to militant political activity. Simply put, the more Jews were murdered in the ghettos, the less personal obligations were felt by survivors, and the more the feeling of responsibility for causing further anguish from Nazi reprisals receded.

Contempt was shown for the self-determined martyrdom of Adam Czerniakow, the Judenrat leader who committed suicide in July 1942. For young Jewish socialists such as the prominent Bundist Marek Edelman, Czerniakow had “made his death his own private business,” a symbol of privilege in contrast to Edelman and his working-class comrades awaiting their turn on the deportation lists. For them, he said, the overwhelming sentiment in these times was that political leadership necessitated that “one should die with a bang.”

The Uprising

In many senses, the hopes of the Left in calling for a common struggle against Nazi barbarity had outlived its constituency: the Jewish community was in the process of being exterminated. What now mattered was the initiative young leftists took upon themselves — and the majority favored an uprising.

On the morning of Monday, January 18, six months after the first mass deportations of Warsaw Jews (which reduced the number of ghetto inhabitants from four hundred thousand to approximately seventy to eighty thousand), ZOB militants emerged from the crowds of deportees to attack German soldiers, killing several. A series of attacks followed over four days, where militants infiltrated lines of slave laborers marching towards the Umschlagplatz [Deportation of Jews], stepped out of rank at a given signal, and assassinated their German guards. Though scores of ZOB fighters fell, the confusion created by the fighting allowed some to flee — and demonstrated to others that Nazi bodies could also fall in the ghetto.

By April 1943, there was a general awareness that the ghetto was to be entirely liquidated. A general armed revolt was scheduled to happen at the next Nazi provocation. On April 19, five thousand soldiers led by SS general Jürgen Stroop entered the ghetto to remove the final inhabitants; in response, approximately 220 ZOB volunteers began their attack, located in ersatz positions in cellars, apartments, and rooftops, each armed with a single pistol and several Molotov cocktails.

The revolt caused chaos, catching the Nazis off guard and killing many Wehrmacht and SS soldiers. In response, the humiliated German army, suffering losses at the hands of prisoners they thought long defeated, initiated a policy of systematically burning out the fighters. To paraphrase one ZOB militant, it was the flames — not the fascists — whom the fighters lost out to. Vicious hand-to-hand combat raged for days, and by late April coordinated warfare by the ZOB collapsed, the conflict now largely consisting of the Germans burning small groups of armed Jews out of bunker hideouts created to evade capture.

According to accounts, both the red flag and the blue-and-white flag of the Zionist movement were raised over ZOB-seized buildings. The youngest fighter killed had been a Bundist activist aged thirteen. Though clearly inexperienced as a fighting force, an anonymously authored Bund internal document that reached London in June 1943 stressed the “exemplary” political unity and “fraternity” between leftist groups in combat. The unswerving dedication to which the young fighters of the ZOB clung to their dreams of socialism was exemplified most movingly in a May Day rally held amid the ghetto’s ruins.

Participating in the rally, Marek Edelman reflected that

The entire world, we knew, was celebrating May Day on that day and everywhere forceful, meaningful words were being spoken. But never yet had the Internationale been sung in conditions so different, so tragic, in a place where an entire nation had been and was still perishing. The words and the song echoed from the charred ruins and were, at that particular time, an indication that socialist youth [were] still fighting in the ghetto, and that even in the face of death they were not abandoning their ideals.

Leading militants of the ZOB committed mass suicide on May 8, surrounded by the German army at their base on Mila 18. By mid-May, the ghetto had been razed, and the Great Synagogue of Warsaw personally blown up by General Stroop on May 16 to celebrate the end of Jewish resistance. A mere forty ZOB combatants had escaped onto the “Aryan” side of Warsaw, where scores more fell before war’s end in the subsequent city-wide uprising of 1944.

The Lesson

In our times, war criminal George W. Bush can pay comfortable tribute to the fighters of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. So can fellow humanitarians David Cameron and Barack Obama, who both offered speeches dripping with moralism about the heroism of the revolt. Their platitudes are the product of the historical reduction of the event over time — something which is likely to increase as more witnesses to the Holocaust leave us, often with unrecorded testimony.

More dangerous still are active attempts to erase the politics that produced such heroic resistance. Just this week, the University of Vilnius in Lithuania announced that it would honor Jewish students murdered in the Holocaust — as long as they had not participated in left-wing political activity or anti-Nazi militancy.

Against this attack on history, the Left’s task is to defend the fighters of the ZOB from the condescension of official patronage or the dark possibilities of state demonization. We can only do this by restating what so many of these people were — young militants, committed to left-wing ideals, brimming with enthusiasm for a better world, pushed to oblivion alongside their community.

Jews by birth and communal affiliation, they also engaged in the struggle as internationalists, a determined part of a worldwide struggle against fascism and capitalism. As weakened as they were, their attitude — that to submit meant death, that resistance even in the face of impossible odds was a moral imperative — inspired imprisoned Spanish Republicans, French communist peasants, their fellow Poles watching from behind the ghetto walls, and their fellow Jews languishing in the concentration camps.

Their story is a reminder of the Holocaust’s brutality and hopelessness, but also a shining example of those who in the worst of circumstances — in the words of the partisan poet Hirsh Glik — could never say that they have reached the final road.