School Could Be Out Forever for These Bedouin Kids in the West Bank

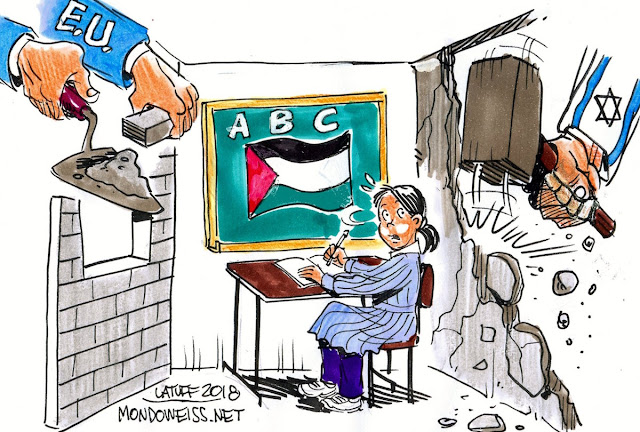

The Zionists International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance definition of ‘anti-Semitism’ says that ‘criticism of Israel similar to that levelled against any other country cannot be regarded as antisemitic’ with the clear implication that other criticism is anti-Semitic.The problem is of course that Israel is not ‘any other country’. It is unlike all other countries being a settler colonial state. In what other liberal democracy, which is what Israel claims to be, would you have whole villages of an ethnic minority demolished in order that a racially exclusive town could be built on top of it? That is what is happening to Bedouin villages in Israel’s Negev.

What other country would have a segregated education system and a situation where Arabs and Jews live apart? But this is only inside Israel. In the West Bank there are two separate legal systems. One for Jewish settlers and one for the Palestinians. Apartheid? Perish the thought. That is why Israel demolishes Palestinian schools.

They have no permission to be built because in Area C, 60% of the West Bank, permits to build aren’t given to Palestinians unlike of course Jewish settlers. So t his is why school could be out forever in parts of the West Bank? Is it anti-Semitic to criticise that? I will leave that up to you.

Tony Greenstein

Israel wants to demolish the school in Al Muntar, with alternatives located too far away for the children to attend. Residents believe they face expulsion because of expansion plans for an adjacent settlement

By

Amira HassFeb 06, 2018

First- to sixth-graders from the Bedouin community of Al Muntar have received a three-week reprieve. During this time, they’ll be able to study without fear that bulldozers could show up at any moment and raze their West Bank school to the ground, turning it into a pile of bricks and timber.

The reprieve – an interim injunction that freezes demolition orders previously issued by the Civil Administration – was handed down by Supreme Court Justice Uzi Vogelman last Wednesday, less than 24 hours before the demolition was scheduled to take place.

What will happen after these three weeks elapse? Everything is in the hands of Allah, says Umm Ayish, a 55-year-old grandmother whose children and grandchildren dropped out of school because the only institutions were sited several hours away on foot or by donkey, accessible only via slippery and steep paths.

In addition to Allah, the fate of the school also lies in the hands of the High Court of Justice, the Civil Administration and the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories. Will they be persuaded that even the children of this Bedouin community in the Judean Desert are entitled to regular studies under reasonable conditions – without reaching school tired after an early wake-up call and a long journey on steep paths; and without having to return home after dark with no power to generate the light by which they might do homework?

On Wednesday morning, hours before the reprieve was announced, pupils’ voices could be heard coming through the windows of the condemned school as some of their fathers and brothers sat on a nearby hill, reminiscing about the hardships they underwent trying to get an education. Most of them dropped out due to the difficulties of getting to the elementary school located in Wadi Abu Hindi, a community situated 3 kilometers (1.8 miles) to the north, and the high school in Al Sawahra, some 15 kilometers to the west.

|

| Two Bedouin children walking home from school in the West Bank village of Al Muntar, January 2018. \ Moti Milrod |

The students sounded happy and carefree. However, according to the community’s mukhtar (elder), Abu Hassan (Mohammed Hassan al-Hadliyeh), the children are well aware of the situation. “They ask me, ‘Will the school be demolished tomorrow?’ And then they tell me, ‘If so, we’ll go to sleep and that’s that,’” he relates, adding that “if the school is torn down, their future will be destroyed. Our girls will stop going to school. In the past, the Bedouin didn’t send their girls to school, but we’ve changed. In Saudi Arabia they let women drive now, and we understand that we must allow girls to study.” They recognize the value of an education not only at elementary-school level but also in high school and university too.

Dahoud is 45 and regrets having dropped out of school. “True, we learn from experience and from nature, and know things others don’t. But nowadays people don’t care what’s inside of you, every employer wants to know what diploma you have,” he says.

Abdallah, 39, wears a hippie-esque green kaffiyeh over his curly hair and says he’s a tour guide.

“There’s a school in [the nearby settlement of] Ma’aleh Adumim, a place to get an education,” he says in fluent Hebrew. “All we’re asking is that we have a kindergarten and school as well. If you had a 6-year-old child who had to walk 6 kilometers both ways to get to school, wouldn’t you be concerned and want to change that? This applies to winter and summer, with the risk of slipping in the rain or dehydration while going to school. We’re asking, with respect and love, to get what everyone else has. We’re not asking for the moon.”

|

| FILE PHOTO: Students at the only school in the Bedouin village of Al Muntar in the West Bank, January 2018. \ Moti Milrod |

Due to the hardships involved in accessing school premises and the high dropout rates – a third of the hundred children of school age – the village of Al Muntar, along with Al Sawahra, decided to build a school in the heart of the community. In 2013, they built some shacks for a kindergarten. This led to a change in the local people’s aspirations and needs, with parents preferring that their small children play together, supervised, in the mornings.

According to documents at the Al Sawahra council, the area allocated for the school and kindergarten is owned by one of the village’s residents. In contrast to the school in Wadi Abu Hindi, situated in a ravine where rainwater congregates, the new area is on a plain. The European Union provided funds and the Al Sawahra council handled construction.

|

| A desk and chairs outside the only school in the village of Al Muntar in the West Bank. Bedouin attitudes to education have changed in recent times, especially in relation to girls. \ Moti Milrod |

The Palestinian Authority’s Education Ministry appointed a principal and teachers, who travel in together daily on a pickup truck that trundles along the rocky and unpaved road. It was also decided to dedicate one of the rooms to a permanent clinic. Currently, the community has a mobile clinic that visits only twice a month.

However, like all Bedouin communities in the area, the village of Al Muntar is not recognized by the Civil Administration. Some of its residents, hailing from the Al Sawahra area, have been living here since before Israel was established. Most of the village’s residents belong to the Jahalin tribe, which was expelled from Tel Arad in 1948, subsequently settling on the edge of the Judean Desert in the early 1950s. Abu Hassan was born in Al Muntar in 1968 and is a son of these refugees. When he was 7, he witnessed the start of construction in Ma’aleh Adumim.

The years passed and Ma’aleh Adumim expanded, leading to further waves of expulsion. In 1990, the settlement of Kedar sprang up right across from Al Muntar. The area had already been declared a closed military zone, though no military exercises are conducted there. The structures and sheep pens in Al Muntar have been torn down several times and the flocks confiscated. But the residents were determined to remain in the place that has been their home since the ’50s. A few years ago, they negotiated with the Civil Administration to try to find a way of staying; it was agreed they would not be evacuated. However, any construction – including public buildings such as schools or clinics – remains prohibited.

|

In December 2016, inspectors from the Civil Administration placed stop-work orders on the kindergarten (which was already operating) and a school being constructed. This led to the standard legal-bureaucratic process of a request being filed for a building permit, this request being denied, an appeal being lodged, the appeal being denied and then, last July, a petition being filed at the High Court of Justice. The school and Bedouin community are represented by lawyer Yotam Ben-Hillel. In the petition, he argued that “in several Jewish settlements and outposts, there are schools and kindergartens that violate planning and construction laws. In many cases, these schools operate with the approval of Israel’s Education Ministry, which funds them and pays for their teachers. The [petition’s] respondents have no intention of demolishing these [buildings] for the sake of maintaining public order,” he wrote.

Following the filing of the petition, the High Court ordered a demolition freeze on condition that construction was stopped. On December 27, justices Yoram Danziger, Neal Hendel and Yael Willner accepted the state’s arguments and denied the petition. They argued that the school was on state land and that the petitioners had continued building despite the court’s prior instructions. The judges wrote: “This is a place that served as a school, but that does not justify the means used or the taking of the law into one’s own hands. One action could create new needs, and so on, with everyone building as they please. The right thing is for the entire issue to be regulated through the legal system.”

The judges did not refer to Ben-Hillel’s claims of inequality – both in regard to planning and building opportunities given to Jews, in contrast to building prohibitions on the Palestinians; and the presence of unauthorized educational structures in the settlements and outposts that operate unhindered and are not threatened with demolition.

|

| The Bedouin village of Al Muntar, with the settlement of Kedar in the near distance. \ Moti Milrod |

Even before the ruling, Israel announced that the kindergarten would not be demolished. Regarding the school, the court gave the petitioners until February 1 to vacate the premises. In one final, desperate attempt to save it, the residents asked the Civil Administration to allocate the 2 dunams (0.5 acres) on which the school stands to them, in order to meet the public need for establishing educational institutions. They also asked to be excluded from the firing zone. They also presented a detailed plan for the school structure and asked for the demolition order to be frozen. They received no reply, whereupon Ben-Hillel filed a second petition last Wednesday morning. Justice Vogelman has instructed the state to reply within three weeks.

Construction at the school has stopped. The yard remains unpaved and no stairs have been built to the classrooms. In the meantime, only 33 students – mainly girls – attend the unfinished school.

Several fifth- and sixth-grade girls said that “the Jews want to demolish the school in order to evict us from here.” Abu Hassan, meanwhile, concludes that “they want our land in order to expand Kedar. Sometimes the inspectors come and tell us to go to Azzariyeh [near East Jerusalem]; sometimes they mention Nu’eima, north of Jericho; sometimes they say Al-Jibal, near the Abu Dis garbage dump. They say it’s for our own good. But I know what’s good for me: It’s to live where I was born and where we’ve been living for almost 70 years.”